Our last inductee to the 25 Year Club for 2017 is arguably the crowning achievement of Mitsubishi Motor Company’s illustrious 100-year history, the Lancer Evolution. Birthed as a pure homologation model for rally racing, it transformed an otherwise innocuous economy car and turned it into a worldwide hero. It drew no quarter and was as close as you could get to having a rally car for the street.

Since Mitsubishi had no idea its creation would become a quarter century-spanning icon, the first one was called, simply and without suffix, the Lancer Evolution. Later generations would go onto become the poster boy of the tuner movement in the 2000s, break countless records around the world, and rewrite the rulebooks for what a fast car was supposed to look like. The legend of the “LanEvo” as it is called in Japan — or for English speakers, just “Evo” — started here.

Since the first three, um, evolutions of the Evo were similar, we’re going to cover the original Lancer Evolution, Evolution II and Evolution III together in this 25 Year Club welcoming.

Mitsubishi didn’t just start building the Lancer Evolution out of nowhere. By 1992, they had been finding success with Lancer rallying for 20 years.

Just look at the results: In 1973 at the Australian Southern Cross Rally, Mitsubishi swept the podium. Andrew Cowan alone had five consecutive titles between 1972 and 1976 with a works Lancer. Nor can we forget the Flying Sikh, Joginder Singh, who was a force of nature when tearing through his home turf of Africa in the Safari Rally, winning it twice. And this was all accomplished in a small Japanese sedan barely modified from stock.

The Lancer Evolution’s immediate predecessor, the Galant VR-4, was the result of Mitsubishi finishing development of their Group B Starion just as the series was being cancelled. With the lemons of a nearly finished race car that didn’t have a series, they made lemonade.

The 4G63 engine and AWD system was adapted into the Galant VR-4 for use in FIA Group A racing. The car soon went on to make a serious wake in rally. By 1992, however, stages were getting narrower and more demanding. This, combined with Toyota and Subaru electing to use a smaller chassis, meant that Mitsubishi had to downsize as well. They re-adapted everything that made the Galant VR-4 special, and put it into the smaller, slipperier Lancer chassis.

The Lancer was 10 inches shorter, and even the porkiest of the LanEvos were 535 pounds lighter than the outgoing Galant VR-4. Combine this with a 247-horsepower mill and all-wheel-drive, and you have yourself a land-based cruise missile capable of 142 mph.

Imagine the shock of being the first guy in a Porsche next to one at a stoplight, laughing to yourself at the economy car, then having your doors blown off. I can only imagine this had the same effect on unsuspecting sports car buyers that Black Tuesday had on American stock investors in 1929.

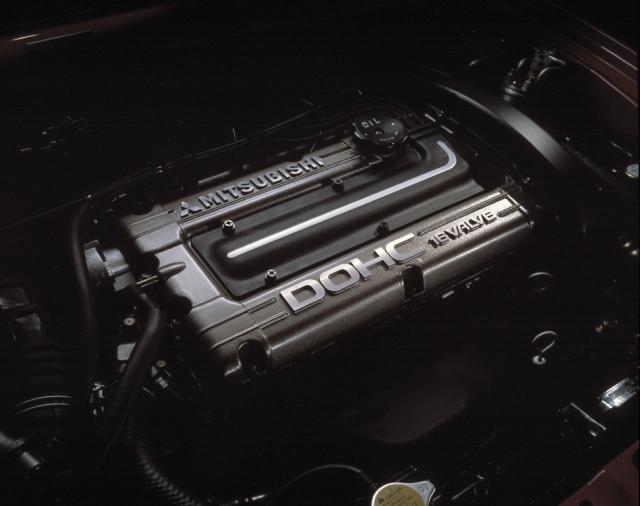

At the heart of it all was Mitsubishi’s most famous mechanical creation, the legendary 4G63 engine. The mill is a checklist of petrolhead dreams — closed deck iron block, DOHC aluminum heads, four valves per cylinder, turbocharged with a front mount intercooler, and fuel injected with a distributor-less ignition system. There was no part of the 4G63 that was phoned in, which is probably why it was in production from 1981 until 2015.

The engine made staggering numbers when modified. Before you even cracked open the block, horsepower figures into the over-500 range could be realized. Once you did delve into the internals, well, there’s been no shortage of drag racers getting four digits on the dyno. Due to its nearly square bore-to-stroke ratio, it’s all too easy to safely rev a well-built 4G63 north of 10,000 rpm, making it even more of a cracker.

Yes, there are other engines on this earth capable of 1,000 horsepower and redlines north of 10,000 rpm, but very few are like the 4G. They’re either factory tuned to their maximum potential, or are more complicated than the mathematics of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. Not the 4G63, though. You can find 40 horsepower merely by sneezing on one.

The cherry on this Mitsubishi sundae is its ease of maintenance. You can more or less fix it with a hammer, and parts can easily be found in any suburb in the country.

Mitsubishi didn’t get lazy outside of the engine bay either. The AWD system, adapted from the original Starion Group B car, took what should have been a wheel spinning mess and created Usain Bolt’s genetic father with a 0-60 time just above 5 seconds.

The rest of the design was basically identical to the Galant VR-4’s. They all featured the same manual transmission, same MacPherson strut and multi-link suspensions, and two types of limited slip differential depending on trim.

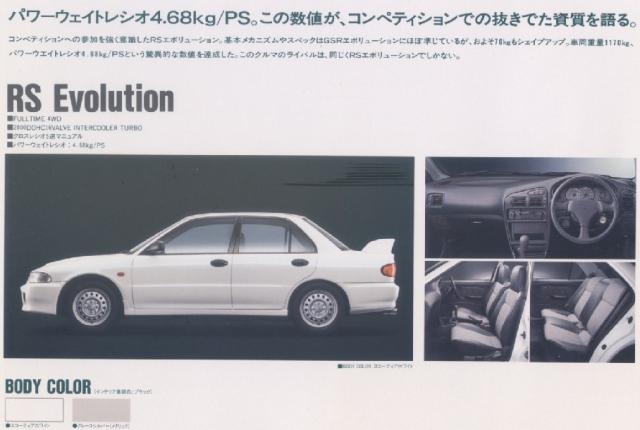

Not only did the Evo come standard with enough performance goodies to ruin the day of most unsuspecting yuppies, Mitsubishi sold an even more hard core version. The Lancer Evolution RS was a completely stripped down variant ready to hit the track. The windows opened via crank, the anti-lock brakes were deleted, as was the rear wiper, and alloys were tossed in lieu of steel (Mitsubishi assumed an aftermarket wheel would replace them anyway). The fat trimming paid off, with the car weighing 154 pounds less than the top-level GSR trim.

It is also worth mentioning that the RS came with a mechanical LSD, as opposed to the GSR’s viscous coupling diff. Although the average driver would nary notice the difference, at it’s limit the mechanical LSD showed its superiority. The RS would continue throughout all generations of the Lancer Evolution and count for some of the most highly sought-after variants on the market.

Since the car was produced purely for Group A homologation in WRC, Mitsubishi never advertised it on TV or at dealers. Still, word quickly spread among enthusiast communities, and all 2,500 in the initial run sold out in just three days. In response, Mitsubishi built an additional run, for a total of 5,000 units sold.

Mitsubishi immediately sent it into battle, serving as their new gladiator from 1993-94, and there was no shortage of promise shown. In its very first race in the modified Group A of WRC, Kenneth Eriksson and Armin Schwarz finished fourth and sixth in the multi-terrain Rally Monte Carlo. Though the Evo didn’t podium in its maiden season, it still managed to take fifth in the Manufacturers’ Championship points standings.

In showroom stock Group N, it was a different story. As one would expect of what was a race car in street-legal guise, the Lancer Evolution easily notched a string of wins across the globe. It swept the podium first through third in Finland’s 1000 Lakes Rally, and repeated the feat at Rally Australia. It even returned to the original 1976 Lancer’s stomping grounds at the grueling Safari Rally, with Kenjiro Shinozuka coming in second overall.

If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. That was Mitsubishi’s philosophy when updating to the Lancer Evolution II in January 1994. It wasn’t so much a generational revamp, but minor adjustments made in preparation for the 1994 WRC season. Revised engine internals and a new intake unlocked nine horsepower. For stability, wheelbase lengthened by 10 mm, and track increased with wider tires wrapped around OZ wheels. Body rigidity was improved, gear ratios were reduced, and sway bars were lightened. The mechanical plate-type LSD became standard, making cornering ability even more supernatural.

Visually, it was nearly identical to the Evolution I, with only the rear spoiler made slightly more pronounced (a trend that would continue through the Evo’s growth). One of my favorite styling features of the entire Evolution series can be found on this car, where “Evolution II” was embossed onto the bottom of the spoiler. It’s a minor addition, but it really brings the back together.

The Evo II picked up in WRC right where the Evo I left off, in May of the 1994 season, clawing up the ranks with ever more wins and podium finishes. Results came at a steady pace as the Evo II’s service continued into the 1995 season as well. That year, however, was notable for the appearance of a new Finnish driver, one Tommi Mäkinen, a name that would become synonymous with the Evo, pilot one for the first time. Mäkinen was lightning fast, slinging the Evo around like he’d been born in it. As a result, Mitsubishi was able to pick up three podium finishes, including a 1-2 sweep in its final race at in Sweden.

Next up was the — you guessed it — Lancer Evolution III. By the time it debuted in January 1995, Mitsubishi had abandoned any notion of keeping the car low key. Most notably, far more aggressive bodywork included a larger intake in the front fascia and an even larger rear wing. It was starting to resemble the over-the-top designs that Evos are known for, but it wasn’t just there to say, “I appreciate EDM and shoplifting”; it provided measurably improved downforce.

The compression ratio was bumped to 9.0:1, astounding for a turbocharged engine of the era, even as the boost pressure was turned up. Horsepower clocked in at 270 horsepower, a hair’s width from the limits of the Gentleman’s Agreement.

With the Evo III, Mitsubishi also introduced its Post Combustion Control System (PCCS), an anti-lag system via a secondary air supply that fed oxygen directly into the exhaust to keep the turbo spinning, ultimately reducing lag.

It was technology previously seen only on F1 cars, but because the Evo was a homologation special, the system was actually installed on all the production road cars as well. They came disabled by the computer from the factory, but with a Ralliart ECU and some minor modifications, it was entirely realistic to implement.

The Evo III’s racing debut came at the Safari Rally, where Shinozuka ran a hard fought race and came in a close second to Yoshio Fujimoto, the former Mitsubishi driver who had switched over to Toyota’s GT-Four Celica. Eriksson claimed victory in both Australia and on the Hong-Kong-to-Beijing Rally, while Mäkinen took the Rally of Thailand.

Erikssen and Mäkinen placed third and fifth in the Drivers’ Championship, with Mitsubishi hot on the tail of the Subaru Impreza WRX STi in the Manufacturers’ Championship. The stage was set for what would become one of the most epic battles and fiercest manufacturer rivalries in history.

It wasn’t long until the entire world was abuzz about how great the new Evos were. In the 1995 movie Thunderbolt, Jackie Chan played a Mitsubishi test driver/tow truck driver/kung fu master who spent about a third of the movie thrashing about an Evo III.

On this side of the Pacific, the best known appearance of an early Evo was in Initial D, when Team Emperor came to Mount Akina to show up the street racers of Gunma Prefecture. Kyoichi Sudo’s Evo III with its anti-lag system was the first car to ever beat hero Takumi Fujiwara’s AE86.

While the first three Evos aren’t nearly as well known as the IV-X models, they were the basis of what would eventually become the most successful Mitsubishi of all time. As for Mitsubishi’s goal of competing in WRC to improve its global reputation, well, mission accomplished.

Being 25 years old, the Evo I is now eligible for importation to the United States. However, these early Evos are extremely hard to come by today. If you can find one, you’ll be gifted with one of the most capable Mitsubishis ever created. Looking at Mitsubishi’s current state can be disheartening, we know. But the company was It was once capable of greatness. The Lancer Evolution is a cloudless reminder of what is possible when the company is truly on top of their game.

Some images courtesy of Mitsubishi, Cusco.

I want one! what more can i say.

I still can not wrap my head around how/why Subaru did SO well with the WRX/STi, and Mitsu went so far off the rails with the performance crowd…

Subaru had other cars in their lineup that people wanted to buy, so they could support the R&D required to continue their performance cars (and develop new ones with Toyota). Mitsubishi let their product line languish, made poor decisions lending to sub-prime customers, and seemed to treat the US market as an outpost that only required half-hearted attention.

I think the downfall started with the Evo VII, as it was the first that wasn’t at all successful in the World Rally Championship. Once Mitsubishi pulled out of the series the Evos became less relevant (even if the road cars were still remarkable) and once the rallying connection had disappeared entirely, there was little incentive to carry on.

To be honest, I’m surprised Subaru has carried on with the WRX/STi for as long as it has. Again, that car lost relevance as soon as the hatchback WRX debuted and they too pulled out of the WRC. It’s improved since, but the current STi is nowhere near as competitive in the modern market as its predecessors were ten or twenty years ago. The difference, as Ben mentions, is that Subaru’s *other* vehicles have remained popular so the performance models have been allowed a stay of execution.

Dammit, Ryan. Now I want an Evo III. Thanks a bunch.

I’ve always wanted one of these earlier Evos…and now he’s jumpstarted that again. Well done Ryan!

I prefer them to the IV and up, which cannot hide what they really are. Let me guess, Evo III in Dandelion Yellow?

Even the name of the color is perfect!

Yeah… now I want one too. I just need to think of modern Mitsubishi to get myself off of the Mitsu train.

That red Evo II with the white O.Z. wheels takes me back. I’m pretty sure one of those was one of the first cars I “bought” in Gran Turismo 2 as a kid.

Also, I’m dumb. I watched the Initial D episodes with the Evo fairly a few months back and scratched my head as to why they were referring to it as a “LanEvo”. It didn’t even slightly occur to me that it was a contraction of Lancer and Evo…

Remember, japanese know that there are two Evolution model, lancer & pajero(also known as montero for Spanish speaker & shogun for UK), hence “LanEvo”&”PajEvo” exist

For those looking for an interesting JNC in U.S. spec, check out the Galant VR4 mentioned in the article as the papa of the EVO line. Fairly rare, only 3000 were imported over two years, two thousand in 1991 and a thousand more in 92. The car is well supported and nearly indestructible. Just don’t bust the timing belt. (Don’t ask me how I know.) Engine is the bullet-proof 4G63T, body’s seem to hold up well, and the interiors wear like iron, including the leather seats. Fast and fun to drive, these things make great daily drivers. When I owned mine, rainy days meant days to go for long fun drives.

Also these things are very affordable. High mileage examples fetch a thousand or two. Nicer examples with less than 150K can go for a little more. But finding a stock example could be a challenge. A nice stock example with just 70K sold last fall for around $10 K. It was a bargain at that price. For more on this great JNC, check out galantvr4.org.

I cannot wait until 2020 so I can import an Evo III. Yellow with white wheels. I will sell my AE86 to fund it.

I would love to have an Evo III, but I’m VERY happy with my ’91 GVR-4. (@ Mike in Long Beach) Don’t know where you saw a GVR-4 for a thousand or two, the only ones I’ve seen under $3000 were parts cars (blown engines, broken drivetrains, extreme rot, crash damage or any combination of the four maladies). I’ve seen a few JDM versions Stateside, with asking prices of 12,000-15,000. I searched for three years before I found a suitable GVR-4 (I’m VERY picky). I paid $7200 for mine in 2014 with 100,000 miles, found it in Miam, FL. It was originally a Cali car. I bought it from the owner of a tuner shop, he bought it in Cali from the original owner. It was all original when he bought it, he then replaced the front seats with new Recaros, added a Momo wheel, AEM series 1 ECU, Greddy electronic boost controller, intercooler and blowoff valve. Did a three angle valve job, belts and seals, upgraded to the 16G turbo, RCI injectors, ACT clutch and light Fidanza flywheel, new struts with lowering springs, 17″ Motegi wheels, HID lighting system, and he installed a top of the line Pioneer sound system, touchscreen with nav, Bluetooth and DVD, sub in the trunk and backup camera. He had the car a year when I bought it, it was well sorted out. I’ve really enjoyed the car, it turns heads everywhere I go (black on black with dark tint and the black Motegis). With the mods he did, it dynoed at 346 HP, and I’m only running 24 lbs. of boost. It’s capable of a lot more, but I like it just as it is, for daily driving. Only issues have been a leaky factory sunroof (clogged drain), and had to replace the drive shaft supports and did the u-joints at that time as well. Good ones like mine are out there, but you DO have to dig a bit, and be patient!

There is some missing information that needs to be shared. The group B Starion 4wd car used a Montero transfer case on the Starion 5 spd trans and Montero front diff and was very modified for the class. Now, in 1984, the same year as the rally Starion Mitsubishi started to place an AWD drive train into the Cordia turbo (GSR) to where the car used a live rear axle from the RWD Lancer and a transmission like the Evo I/VR4 used. This was in a production road going vehicle (and even the Tredia turbo). So the EVO lineage has it’s roots in several different cars of the era. Any information on the AWD Cordias is stupid hard to find, even on the Cordia power site. As far as I know there are only a few AWD Cordias left in the world, and just 2 FWD turbo ones in the states (I have one).

I could have easily done an article on the evolution of Mitsubishi’s AWD systems but I had to stick to the highlights prior to the Evo. The AWD article will be in the works though so don’t worry.

I look forward to that article. Although my Cordia is not AWD, if you need any photos of any systems let me know.

Evo and WRX. The most famous JNC rivalry.

I’m pleased that they joined the 25 year club.

Red and blue. Mitsubishi and Subaru. These two rally weapons will be a legend of the new generation JNC like Hakosuka and RX3.