The 1964 Summer Games in Tokyo was a turning point for Japan. They were the first Olympics to be held in Asia, and Japan was ready to rejoin the world as a symbol of modernity. As a show of its recovery, Japan’s industrial titans saw the Olympics as an opportunity to present their best wares, and the carmakers seized it.

In the lead-up to the 18th Olympiad Japan pulled out all the stops — expanding the Tokyo subway system, creating the bullet train, constructing Japan’s elevated expressways. It was the first event to be televised via satellite across the globe, and Japan knew the world would be watching.

There was no aspect in which Japan did not give it its all. Even the official Olympics poster was a triumph in graphic design. Replacing the traditional classical artwork evoking ancient Greece — think pillars and marble statues — was Yusaku Kamekura’s thoroughly clean and elegantly minimalist modern style. 1964 also launched the widespread use of pictograms at the Games, icons helping people navigate the venues without knowledge in any specific language. These innovations sent shockwaves across the design world.

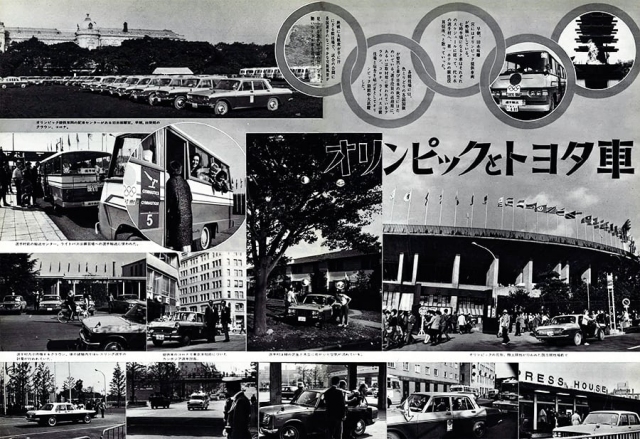

It was against this backdrop that Japan’s carmakers put forth their finest creations, showcasing them before a global audience like none the country had ever seen. The Games Organizing Committee requested domestic car companies to provide vehicles, and the major Japanese manufacturers responded enthusiastically.

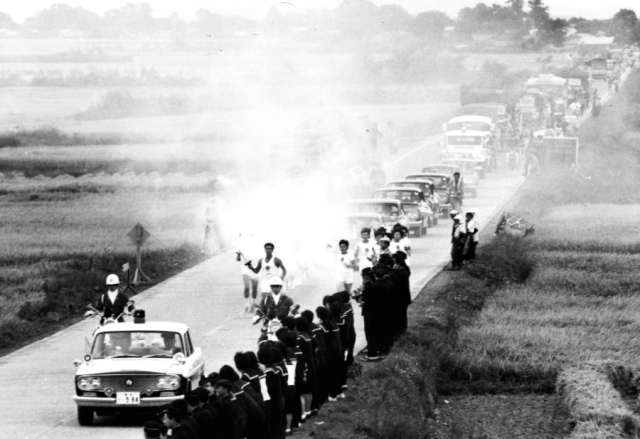

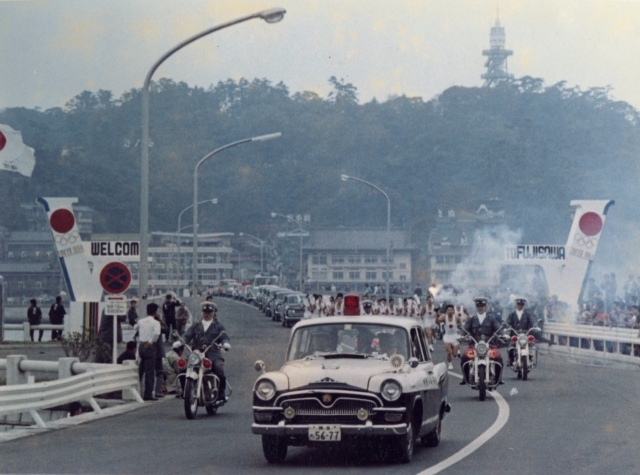

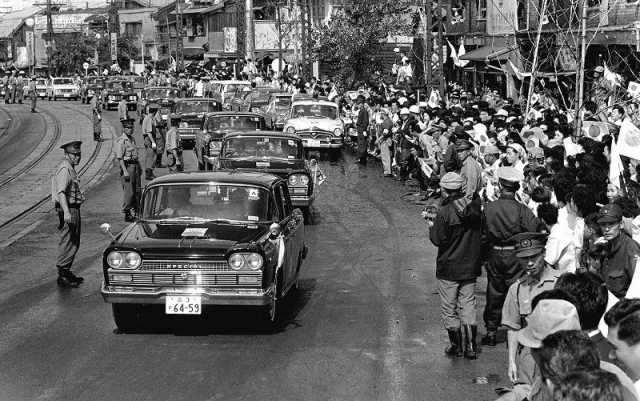

Japan wanted the Olympic torch to pass through every prefecture, and so the planners came up with four routes run simultaneously. All four torches would converge in Tokyo after covering 4,200 miles of ground relays with a total of 4,374 relay sections. Each one needed vehicular escorts, which ranged from local law enforcement to cars donated by the manufacturers.

As Japan’s most powerful carmaker Toyota was expected to be the most generous corporate citizen. It led the way with seven cars for the torch relay, including Corona, Crown, and Crown Eight models. In addition, it contributed 95 other vehicles for use during the Games, including Corona and Crown cars, Masterline and Dyna trucks, as well as Toyopet light buses.

Many of the cars were high-end models, typically chauffeur-driven in those days. The Toyota Crown Eight was the grandest of them all, a V8-powered luxury saloon. Japanese cars with more than six cylinders were still very rare at the time, and its station was on par with that of a Toyota Century’s today.

Size-wise, it stood a full six inches wider than rivals like the Nissan Cedric or Prince Gloria. It also cost about about ¥270,000 more than those two cars. With that kind of presence, there was no question that Toyota was a king among carmakers.

Nissan came to the table with the Cedric Special 6 as the torchbearer’s companion car. As the name implied, it was powered by an inline-six engine, and was an impossibly luxurious sedan by the standards of most Japanese citizens. Many of the routes these cars traveled on had not yet been paved, so the Cedric was modified with special rear dampers to help it traverse the rough roads.

Some of the cars were tasked with carrying a spare torch. To accommodate the special cargo, Nissan came up with an carrying contraption not unlike those used by soba delivery bikes. These devices would help stabilize the hot broth so the soup could travel along bumpy roads without spilling, and kept the torch upright in the back of the Cedric. One of the specially outfitted Nissan Cedrics is still around today, part of Nissan’s Zama collection.

Back in 1964, Prince Motor Company was still an independent entity. The merger with Nissan wouldn’t happen for another two years. Prince’s car of choice were the Gloria Super 6. This generation cost about the same as a Cedric Special 6, but had slightly smaller dimensions.

However, it was the sports sedan of the bunch, helped in part by a 130ps inline-six that would eventually find its way into the nose of an elongated Skyline and turn it into a legendary touring car. It boasted a maximum speed of 106 mph, quite an impressive figure for the era, especially when there were few roads where it could reach such speeds.

In addition Grand Gloria sedans were provided as torch relay escort vehicles, and to the Japan Olympic Committee as a shuttle car for VIPs. One of the original Gloria Super 6 Olympic cars did survive, but unlike other historic Prince cars is not part of Nissan’s Zama collection. It has been restored and is kept by a private owner.

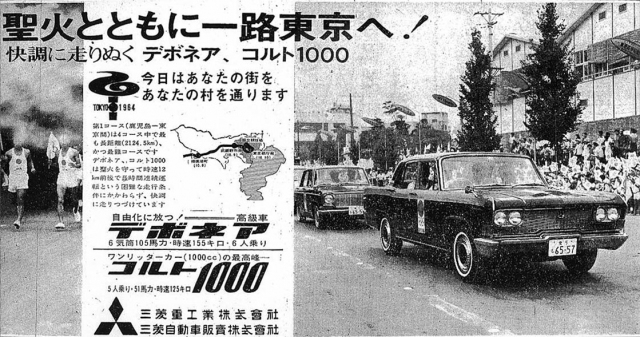

Finally, there was Mitsubishi, at the time just an an automotive division of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. The triple diamond clan contributed the Colt 1000 and its flagship Debonair sedan to the torch relay, with advertising to show that they had taken what Mitsubishi claimed was the toughest route, a distance of 1,320 miles.

Mitsubishi also provided Fuso buses for shuttling athletes, officials, and reporters around. It’s unknown if any of these cars survived. If they did, they haven’t been seen at any car shows in Japan in recent years. Even photographs of these cars are difficult to come by. The only ones seem to be in old newspaper advertisements.

Now, 57 years later, the Olympics have returned to Tokyo. This time around, things are a bit different. In 1964, the country seemed full of hope and optimism. Japan was just a couple of years away from revoutionary achievements in the automotive world, from the Toyota 2000GT to the Mazda rotary engine to Honda’s magnificent Formula One victory to Nissan’s game-changing Fairlady Z. It was the era of bullet trains, expressways, and color TVs.

This year, there seems to be a cloud hanging over the entire event, and not just because the pandemic has left the grandstands empty after postponing the Games for a whole year. Japan’s auto industry no longer seems to be as innovative or daring as it once was.

It’s tempting to read into this, as if the two Olympics are bookends to a great tale that’s coming to a close. But that would be too tidy a conclusion. The world is a nuanced and complex place, and there are still a few bright spots we can look forward to. Here’s to the future.

Images courtesy of the Japan Olympic Committee, Toyota, Nissan, Mitsubishi.

I believe the Prince Grand Gloria (S44P) is a stand alone model above the Prince Gloria Super 6 (S41-D)

Rather than a nickname for the Gloria, the Grand was quite a different machine. Using the 134HP 2500cc G11 engine running a 4 barrel carb through a BW 3 speed auto. Culminating in the longer wheel base S45P. A true flagship and a rare beast indeed! The lower spec Super 6 ran the 106hp G7 through a 4 speed (3+o/d) column shift. A few S41’s and at least 1 S44 survive in Australia to this day!

You are right. A lot of this research came through in roughly translated Japanese so thank you for the correction. It turns out the Grand Gloria was used as a VIP shuttle, and appropriately so!

Well after all that effort, you’d think they could’ve stopped that annoying guy with the humongous smoking cigarette running around spoiling every shot!

I seen one of the Prince Gloria cars used in the Olympics at the privately owned Prince and Skyline Museum Okaya city, Nagano region of Japan, even had special colored “TOKYO” Olympics badging on the rear, fantastic museum by the way!

lol

Great article & a very nice nod to the graphics! Yusaku Kamekura’s work was a game changer as well as the pictograms.

Thank you, glad you enjoyed it