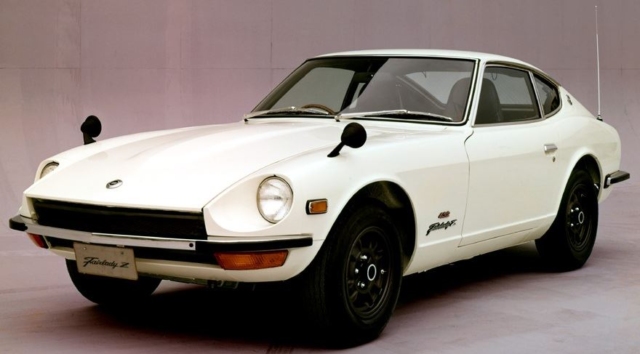

Fifty years ago today at The Pierre hotel in New York City, the automotive world was forever changed when Nissan unveiled the Datsun 240Z. The occasion was the car’s international press launch, where Western journalists got to see the game-changing sports car up close for the first time. A similar event for Japanese press had taken place for the Fairlady Z four days prior in Tokyo, but the October 22, 1969 date is a significant one, as the story of the Z and America are inexorably entwined.

This is not to say that Nissan developed the S30 Z for America, as one the more persistent Z-car myths goes. The 240Z was indeed the torquier, best-selling version of the S30 chassis, but it was an offshoot of the 2.0-liter (for Japanese tax purposes) Fairlady Z. However, the success of the Z could not have happened without America. As our editor-at-large Ricky Silverio says, “You can have individual enthusiasts in other parts of the world singing the praise of a certain model or tuning style, but in many cases unless it does well or is accepted in America, it won’t carry weight to the larger demographic.”

This was never more true than in 1969. America was essentially an omnipotent power, both militarily and economically. We were the purveyors of fashion and culture, and had just hurled a person onto the moon. The rest of the world looked up to us as if we were on a pedestal, a land with streets paved with gold — for almighty V8 machines to power down, naturally.

The primary alternatives hailed from Europe, in the form of European roadsters built on decades-old platforms, or exorbitantly priced exotics doubling the price of a Corvette. Japan was barely on the performance car shopper’s radar.

A few sporting options did exist, such as the Toyota 2000GT, but at $6,800 it cost even more than many of the high-end Europeans. The most successful were Nissan’s own offerings like the Fairlady roadster, which bested the British competition in performance but not in brand strength.

The Z birthed a category all its own, a fixed head sports car with the might of a 150-horsepower straight-six, fully independent suspension, rack and pinion steering, and graceful lines, all for the low, low price of $3,500. It would be easy, and perhaps a little cliché (even more so than calling it, as it is commonly referred to by older writers, a “poor man’s Jaguar”), to say that no car could match its performance and poise for its price. In fact, the “for its price” qualifier wasn’t necessary.

American customers went absolutely nuts for the 240Z, and dealer markups ran rampant. According to the biography of then-president of Nissan USA Yutaka Katayama, Mr K: A Man Who Realized a Dream in America by Takashi Ashikawa and translated by Brian Taylor, there was at least one report of a dealer adding leather seats and a high-end stereo and selling the car for $10,000. By comparison, a Porsche 911 cost about $6,000.

The gouging did little to slow demand. Waiting lists stretched to a year, and Nissan couldn’t make the cars fast enough. In the same book, an anecdote tells of the craze turning Katayama into a minor celebrity: while riding on a jet liner, a flight attendant realized who he was started begging him to move her up the wait list.

America had Z fever, and it was no small feat. A reputation of cheapness, negative sentiments from the war, and occasional racism still hung heavy over every “Made in Japan” label, but the 240Z not only transcended that baggage, but succeeded despite it all.

It is impossible to write a truly comprehensive article about the S30 Z. There have entire books dedicated to the subject. Indeed, it may be the most written-about Japanese car on Earth. Sadly, that also means there are plenty of errors and myths as well.

One oft-told story states that the Toyota 2000GT and 240Z had a common ancestor, and that both were designed by Albrecht Goertz. This has been largely proven untrue by authorities on the subject such as Z historian Alan Thomas and author Shin Yoshikawa, and Katayama himself dispelled any notion that Goertz penned a single line on the S30. Instead, according to Thomas, it was Akio Yoshida and Kumeo Tamura, working under the leadership of Yoshihiko Matsuo who shaped the Z. Decades later, some of them have stepped out from the shadows of Japan’s “team effort” way of thinking to receive proper credit, but the incorrect attributions remain in print and on the web.

Thomas, an often vocal critic of the Ameri-centric version of the events surrounding the birth of the Z, will point out the S30 Z was designed for both markets in mind. He points out obvious clues, such as the locations of the handbrake and intake and exhaust manifold, which are better suited for a right-hand-drive car.

The story of Katayama personally tearing the Fairlady Z badges off the cars as they landed at port is apocryphal, too. Though he was a staunch advocate of using a name more amenable to American ears, Thomas points out there were cars in Japan testing with 240Z badges already. Still, tales like the one about the hood being raised to accommodate the 2.4 (when it was done for the Japanese 2.0) persist.

No story of the Z would be complete without mention of its racing prowess. Katayama, a brilliant marketer and racing enthusiast who helped found the Sports Car Club of Japan and the Tokyo Motor Show, astutely realized that throwing factory support to the most promising grassroots race teams — and developing an encyclopedic catalog of performance parts — would further sear the Datsun-to-sports car hash map into the brains of gearheads.

The west coast-based Brock Racing Enterprises team, which took four SCCA national championships racing Datsuns from 1970-72, and the east coast-based Bob Sharp Racing, winning six from 1967-75, got Katayama’s blessings. Both had raced Datsun Sports 2000 roadsters, and when the 240Z came out they were perfectly positioned to be highly visible and forceful emissaries.

However, as our resident Datsun racing historian and vintage racer Glenn Chiou would say, there were countless more privateer teams that saw incredible success even without the weight of an automaker behind them. The 240Z was such a powerful adversary, it allowed many of its drivers to turn pro, bridging the gap from the SCCA minor leagues to the IMSA majors. Until the arrival of the Mazda RX-7 a decade later, the Datsun 240Z stood as the unrivaled, definitive force in American grassroots racing.

However, the 240Z wasn’t just dominant on road courses. Elsewhere in the world, the 240Z took to rally stages, twice winning the grueling East African Safari Rally, in 1971 and 1973. Zs have drag raced, set land speed records, and participated in just about every type of motorsport there is. On tarmac and dirt, the Z had taken on the world’s best — Corvettes, BMWs, Porsches and more.

The victories helped propel the S30 Z to sales of 550,000 globally, nearly 84 percent of which were tallied in the US of A. By contrast, Nissan moved around 80,000 S30 Fairlady Zs in Japan. In 1974 the 240Z gave way to the 260Z and added a 2+2 body style, but an induction system developed in the wake of the oil crisis hampered the Z’s reputation for reliability. Still, sales showed no signs of slowing as the 280Z and its trusty electronic fuel-injection system took over. By 1983 sales had topped 1 million, and the Z handily took the mantle of the best-selling sports car nameplate the world had ever seen.

The Z had become such an icon, that in 1996 Nissan USA made the unprecedented move of buying back, restoring, and selling 1970-72 models at select dealerships alongside brand new Maximas and Pathfinders. Originally about 200 cars were planned, but due to parts bottlenecks and costs — even at the list price of $27,495 they lost money on every one, and it was during a time when solid Zs were valued at under $10,000 — fewer than 40 were actually sold. Nevertheless, it was an affirmation from Nissan of the 240Z’s preeminent place in the company’s history.

The 240Z was a world class machine that could take on any old world giant on the circuit, and garner admiration and respect on the street, But, it was also a car that anyone could afford and enjoy.

At least, that was the case in the US. In Japan, the Fairlady Z was a bit more unattainable. Japanese citizens got their first glance at the S30 Z in a full-length newspaper ad published October 20, 1969. At release, the price of a base-model Fairlady Z was ¥930,000, a little over $2,500 USD then but still out of reach for most Japanese. A luxury trim ZL with such amenities as a 5-speed transmission and AM radio cost ¥1.05 million ($2,900 USD in 1969).

However, largely unknown in the West until the 21st century, Nissan also built a performance-spec Fairlady Z432, equipped with four valves per cylinder, triple Mikuni carbs, and twin cams. It cost an eye-watering ¥1.82 million ($5,000), or approximately double the price of a base model.

A closer look at the differences revealed why. The high-revving, 160-horsepower motor came courtesy of the Prince-developed S20 in the Hakosuka Skyline GT-R, supported by a modified exhaust manifold and air cleaner, transistorized ignition system for high-speed operation, a 10,000-rpm tach, aluminum radiator, and electric fuel pump. Z432 models were further set apart by their trademark stacked dual-tip exhausts, standard rally clock, magnesium wheels, and countless other differences.

An even harder core lightweight, homologation Z432-R model, offered composite windows, a baffled 100-liter fuel tank, and thinner gauge sheetmetal throughout. Nissan managed to get weight down to 855 kg (1,885 pounds) according to Thomas, who further states that all were finished in orange with satin black fiberglass hood to prevent glare, and each one was built to order with special parts like the glove box and brake booster delete, so no two are exactly the same.

By 1971, the Japan-market Fairlady Z had also adopted the 2.4-liter L24 inline-six. It added an aerodynamic front end called the Grand Nose or G-nose for short, based on the prows of S30 Zs competing in Japan’s Grand Champion series. While the Fairlady Z did have its racing successes back home, achieved mostly with the L24, it was somewhat overshadowed by the utterly dominant Skyline GT-R’s 50 touring car victories.

Nevertheless, though the Skyline holds a special place in the hearts of most Japanese enthusiasts, any classic car show in Japan will have no shortage of Zs, In the US, on the other hand, where neither the Skyline nor S20 engine was offered, the Z became Nissan’s halo car. In both hemispheres, the Z has spawned a thriving aftermarket, tuning, and restoration culture that still endures to this day. That Nissan was able to produce two models that transformed their brand image on two different continents at the same time is a feat unto itself.

In JNC‘s 13 years of existence, we’ve encountered all kinds of people. Sometimes, they’re not into cars at all. “What’s an example of a Japanese classic?” they’ll ask. Skylines and Celicas spark nothing, but Datsun 240Z always gets a nod of recognition. Even among car enthusiasts, many have no idea that rear-wheel-drive Corollas and Mazda rotaries predate Nissan’s sports coupe. Yet, appreciation of the Z is universal.

Thus, it could be said that the S30 Z is the quintessential Japanese classic. Beloved and admired the world over, it completely upended the sports car establishment. It didn’t just become a seminal car in the Z lineage, or even the broader Nissan marque. It changed the way all Japanese cars were viewed outside of Japan, and paved the way for all the Toyota, Mazda, and Honda sports cars we know and love. In other words, as far as Japanese icons go, everything starts with Z.

Some points, if I may:

First of all, what makes the Pierre Hotel event any more “international” than the Press Day at Nissan’s Ginza, Tokyo HQ on 18th October 1969? I’d say the PRESS DEBUT for the new S30-series Z range was that 18th October Ginza HQ event and the PUBLIC DEBUT took place on 24th October when the doors to the Tokyo Motor Show were opened. The Pierre Hotel NY and subsequent LA hotel press events were sideshows.

Secondly, I’d cite Akio YOSHIDA and Kumeo TAMURA – under overall command of Yoshihiko MATSUO – as the two men with most hands-on influence on the exterior styling of the body (Itsuki CHIBA styled the interior) but it is more complicated than that…

Thirdly, you’ve quoted me as saying that the LHD cars were somehow ‘adapted’ from the Japanese (RHD) models, but in fact it is clear from looking at the design, engineering and manufacturing of the cars themselves that each variant seen at launch very cleverly incorporated specs and details which were there because the other variants were designed and built alongside them. So, for example, the LHD cars carried elements attributable to the RHD cars and vice versa, whilst tens of thousands of cars carried details that were there because of the less than 500 Fairlady Z432 and 432-R models produced. There *was* some ‘design concession’ involved (the siting of the handbrake lever on the RH side of the tunnel is a good example) but this was mainly due to the RHD origins of the drivetrain itself, with induction and exhaust on the LH side of the L20A and L24-engined cars influencing exhaust routing and fuel tank offset. If anything the S30-series Z design and engineering should be praised for the success of both LHD and RHD layouts and packaging rather than the “Made for the USA” cliches that don’t stand up to any great scrutiny. The cars themselves tell the story just as much as their creators do.

There’s more to say – there always is! – but thanks for an interesting article, and isn’t it great that we’ve reached the big 50 and these cars still inspire us? A big THANK YOU to the many hands responsible for the creation of these cars!

Hi Alan, I’ve edited the piece to include the corrections and clarifications you mentioned. As you know, there could be many more volumes written about these cars but for the purposes of this article some stuff had to be condensed to make it readable. Thanks as always for your contributions to the subject, and for fighting the good fight against those persistent myths!

Nissan needs a car like this now. Sexy, good performance, attainable price structure. A far cry from the current utterly obsolete and obese “Z” that we have today.

I totally agree.

Great article

I have a 72 – 240z

Thanks, and lucky you!

So many car manufacturers have done a retro with much success , why hasnt Datsun yes Datun done the same ?

Perhaps you missed the likes of the Pau, Figaro, S-Cargo and Rasheen?

Well, I mean I hadn’t even heard of one of those, and they were all Japan only weren’t they? And even then, none of them are sports or sporty cars. They’re all pretty gimmicky really. I would bet most car people have never even heard of them, and none of them ever set the world on fire for enthusiasts.

Nissan had our attention with that retro themed 510 concept but chose to release 12 more compact SUVs instead.

“Ricky Silverio is fond of saying, “You can have individual enthusiasts in Asia, Europe, or Australia singing a brand’s praises, but unless it’s accepted in America it won’t count, even in those places, to the broader public.”

Exactly WHY would he be fond of saying that? Signed Bemused (and Amused).

Good article otherwise….. LOVE the 240 Zed (as we say down under).

Count me as bemused here too. Worth making a note of it for future, er, regurgitation…

I kind of took Ricky’s words out of context and have revised them to be more specific. Nothing negative was intended. The main point is that America has an out-sized influence (on many things) for better or for worse. I’m not trying to make any claims that the 240Z is better than the Fairlady Z.

However, it was the 240Z that changed perceptions of Nissans (and Japanese cars in general) in the West, something that the home-market Fairlady Z couldn’t have done. The GT-R is more evidence. Many in the West thought the nameplate began with the R32. As Alan and others have noted, many didn’t even know there was a Fairlady Z and its variants in Japan until decades after the 240Z had made its impact.

I understood what you meant though. It’s not something restricted to cars anyway, music artists and actors have a similar deal. They can become well known in the UK or other places overseas, but if they don’t make it big in the US they won’t become big, big. For every Chris Hemsworth, who transitioned from soapies in Australia, to what he has, there’s thousands of other actors who would love to achieve that.

The MX-5 has the same history really. Americans loving them made them what they are. They were popular here in Aus, Brits loved em, they went alright in Japan, but it was the US market that gave them their name.

Y’all might like some more of the 50th Anniversary Info at the ClassicZcars.com website:

https://www.classiczcars.com/forums/topic/61338-happy-2019-a-lot-of-50-year-milestones-coming-up/#comments

My 1st Z was a 1970 240 It was by far my absolute favorite car But marriage and children came along and I had to sell it One of the worst days of my life. But there is a happy ending I now own a 2006 350Z Which I will never sell And drive it until I’m too old to drive and the state takes away By license

great article about this vintage beauty, I hope you write more of this more often, I love to read and hear anything that has to do with the Z line, I own a 72 3.2 liter stroker engine in it.

One of these days I’ll have one …

That Veys Realty #39 picture is perfect.

Does anyone have an ACTUAL e-mail address of an ACTUAL 350Z car club IN Japan? Not interested in car clubs in other countries. Your help is appreciated.