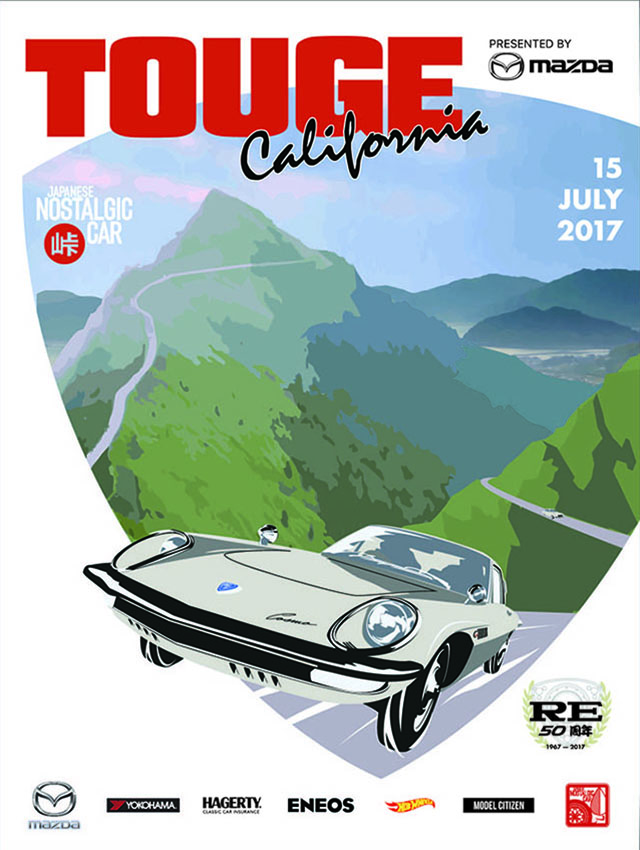

Like it or not, the automotive industry is a highly conservative one. Advances are incremental, radical innovations few and far between. Amidst this seemingly depressing state, however, genuinely novel and creative ideas that challenge convention catch our attention and imagination all the more. Today, we celebrate the 50th anniversary of one such idea — or, rather, its manifestation. Half a century ago today, a dream came true: the Mazda rotary engine and the first car powered by it, the exquisite Cosmo Sport, was put forth into the world.

The dream in question was one held by engineers since the inception of reciprocating internal combustion engines. The premise is that pistons rapidly bouncing back and forth in opposite directions simply seems illogical on first principle. An engine with all its motive parts working in the same direction would seem, mechanically speaking, more natural, even optimal.

Indeed, a non-reciprocating “engine” in the form of a mechanical pump dates back to 1588. Even James Watt, a cornerstone of Industrial Revolution, devised a rotary steam engine in the 1700s. In the modern age, it was German engineer Felix Wankel who had the idea of a rotary gasoline engine with the tried and true Otto combustion cycle. In the end, however, the dream and its real-world adoption would be realized essentially alone by a small company from Hiroshima, Japan.

A Tradition of Precision Engineering

That Hiroshima company would be Toyo Kogyo, or, more specifically, its automotive marque, Mazda. Many readers know that Toyo Kogyo began life as a cork manufacturer in 1920. Within the decade, Toyo Kogyo would branch out into the design and production of machine tools. Over the years the firm broadened its scope to rock drills, gauges, and other precision industrial equipment. In fact, one could trace a direct line from this tradition of precision engineering to the meticulous efforts put into Mazda cars to come.

By 1960, Toyo Kogyo was selling a good number of three- and four-wheeled Mazda trucks, but it was a still small carmaker under constant pressure to merge with a larger entity. Matsuda’s vision was to use Toyo Kogyo’s technical prowess to distinguish itself from the competition and fend off the threat of consolidation.

By 1960, Toyo Kogyo was selling a good number of three- and four-wheeled Mazda trucks, but it was a still small carmaker under constant pressure to merge with a larger entity. Matsuda’s vision was to use Toyo Kogyo’s technical prowess to distinguish itself from the competition and fend off the threat of consolidation.

That’s when Tsuneji Matsuda, president of Toyo Kogyo, sought a license for a newfangled rotary engine from Germany’s NSU, patent holder of the first modern rotary engine design. The other companies granted the license were giants — General Motors, Mercedes-Benz, Citroen. So when Mazda won the coveted licensing agreement in 1961, there was much celebration.

Unfortunately, it would soon prove to have been premature. In late 1961, the first prototype rotary engines from NSU arrived in Hiroshima. Mazda engineers were saddened to discover that the single-rotor unit ran poorly, smoked, and quickly died. Though a wonderful idea, radically different from the reciprocating engine under development for eighty-some years, a non-trivial amount of engineering development, ingenuity, and determination stood between that idea and its realization.

Other automakers that had won the license fared no better. The engine that promised to carry Mazda into the future was instead dead on arrival. For Toyo Kogyo, this was exactly the type of colossal challenge that decades of precision engineering had prepared them for. They would undertake the monumental but fantastic test of turning the rotary engine from a rough concept to viable reality.

Mr. Rotary, Kenichi Yamamoto

To achieve its aims, Toyo Kogyo formed the Rotary Engine Development Committee. Testing and experiments on the rotary began in earnest, but early results were still troubling. The prototype single-rotor engine the team built, based on NSU’s design, exhibited serious issues with vibration and smoke emission. By the end of 1962, Tsuneji Matsuda decided that a full-on research division for the rotary was necessary. The person chosen to lead this division was one Kenichi Yamamoto.

Ironically, Yamamoto originally joined Toyo Kogyo out of pure necessity and not even as an engineer. A mechanical engineer by training, Yamamoto’s original interest and line of work was aeronautics. After the war, Yamamoto returned to his native Hiroshima, to a city utterly devastated by the atomic bomb. Employment was extremely scarce, and Yamamoto was forced to take the only available job: as a line worker in Toyo Kogyo’s transmission factory.

The work was physically and mentally taxing. He labored day in and day out assembling gearboxes and differentials for Mazda’s three-wheeled trucks. He was constantly covered in oil and grime and far removed from actual engineering work — until one day stumbling upon a stack of blueprints. Yamamoto began examining them, carefully checking the specs and tolerances on the transmission components he was assembling.

Eventually, Yamamoto’s diligence was noticed by a senior engineer, leading to an actual engineering job. Yamamoto would go on to design Mazda’s first OHV engine, at the young age of 25 no less. By 1959, Yamamoto became deputy manager of the Engine and Vehicle Design Division. He oversaw several important Mazda passenger car projects at the time, including the R360, Mazda’s first passenger car. Reaching nearly 65 percent market share in the kei car segment, the R360 was a huge success, making Mazda an important leader of mobility in post-war Japan and Yamamoto a valuable player on Toyo Kogyo’s engineering team.

Eventually, Yamamoto’s diligence was noticed by a senior engineer, leading to an actual engineering job. Yamamoto would go on to design Mazda’s first OHV engine, at the young age of 25 no less. By 1959, Yamamoto became deputy manager of the Engine and Vehicle Design Division. He oversaw several important Mazda passenger car projects at the time, including the R360, Mazda’s first passenger car. Reaching nearly 65 percent market share in the kei car segment, the R360 was a huge success, making Mazda an important leader of mobility in post-war Japan and Yamamoto a valuable player on Toyo Kogyo’s engineering team.

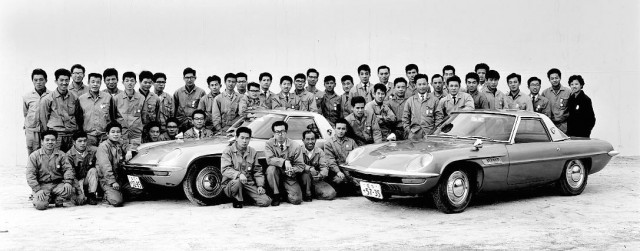

Yamamoto’s talent led Matsuda to entrust in him the task of developing the rotary. More importantly, Matsuda instilled in him a conviction that the Hiroshima company could succeed and remain independent through engineering ingenuity — a noble philosophy that greatly inspired the young Yamamoto. With a specially-chosen group of forty-seven ronin — engineers, designers, and material scientists in the newly established Rotary Engine Research Division, the game was afoot.

Rotary à la Mazda

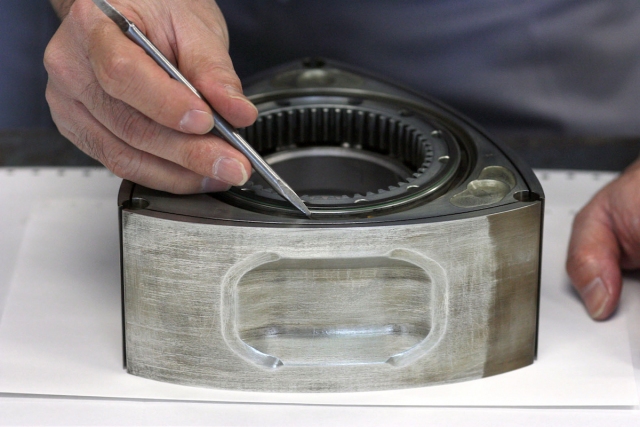

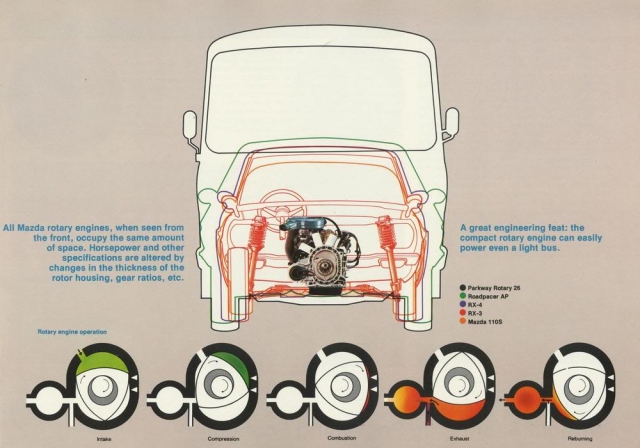

The road to a workable rotary engine was a long one. The basic idea was this: Instead of a series of pistons and combustion chambers turning reciprocating motion into circular motion then output through a flywheel, the rotary engine would spin in only one direction, producing circular motion from the start. Combustion would occur in the chambers created between the rotor and its housing, delivered through the eccentric shaft. The fact that a rotary obviated the need for a multitude of valves, cams and rods was a bonus.

That was the theory, at least. In practice, there were serious obstacles to overcome. Delving into all the trials and tribulations would be a treatise digestible only by the most hard core tech nerds, but the short version is that Yamamoto’s team faced some major obstacles.

The most famous and persistent of them was given an actual name — the “devil’s claw marks” that formed in rotor housing, where the apex seals made contact. Yamamoto’s Materials Research department embarked on a comprehensive search for the perfect apex seal, but in what may or may not be an apocryphal story, a common pencil provided the eureka moment with its carbon (i.e., graphite) core. Extensive testing led to a carbon-infused aluminum apex seal whose strength and smoothness both maintained compression and eliminated the demonic lacerations across the housing.

Still, further hurdles remained. To overcome the excessive oil consumption stemming from the complex oil sealing schemes at the tips and sides of the rotor, as well as between the sandwiching rotor housing and side plates, Mazda called in a collaboration with the Nippon Piston Ring Co. and Nippon Oil Seal Co. To quell vibrations that made the engine unusable, Yamamoto ditched NSU’s single-rotor configuration, as it was inherently unbalanced, and added counterweights at the ends of the eccentric shafts.

It must be noted that these breakthroughs came after years of the Rotary Engine Research Division toiling day and night. Yamamoto’s team was given a sizable budget, grew quickly in size, and burned through hundreds of prototype engines.

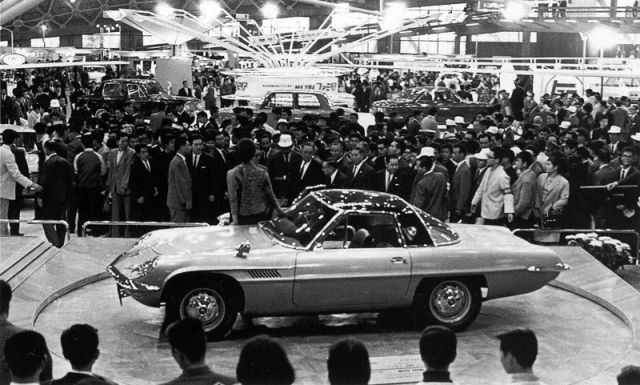

In the end, Yamamoto and his team did Tsuneji Matsuda proud. At the 1963 Tokyo Motor Show, the boss himself personally drove in the never-before-seen sports car prototype, powered by a 796cc rotary engine dubbed the L8A. The car would officially make its debut in the show the following year.

Hello, world. This was the Mazda Cosmo Sport, what was to become the world’s first production car powered by a dual-rotor engine. Then the stunned crowd realized what they were witnessing: a new type of engine turning the small carmaker from Hiroshima into a world leader.

The Most Futuristic Car Ever Built

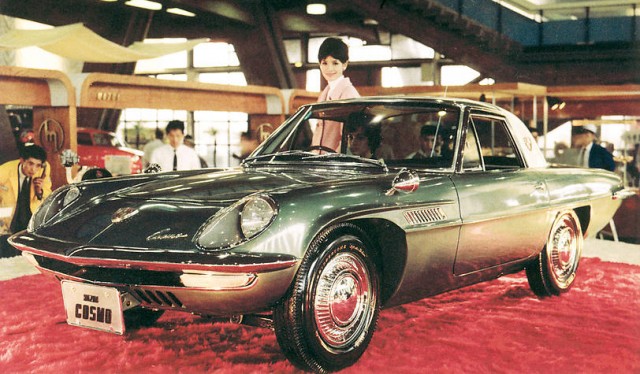

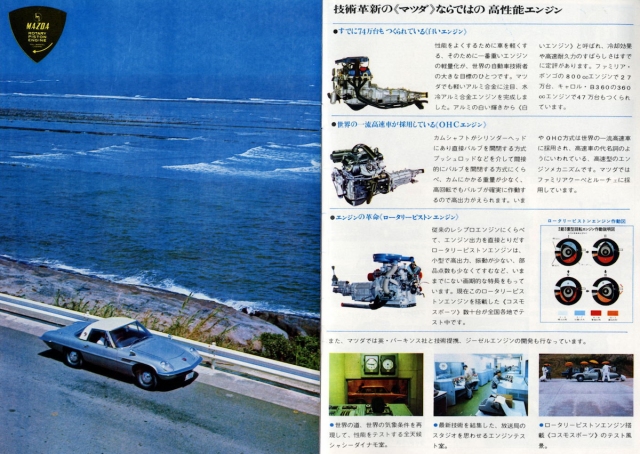

Tsuneji Matsuda must have felt pretty damn incredible stepping out of his car. In appearance, the Cosmo Sport was a nymph of a car, sleek, beautiful, and visionary. The design hailed straight from the space age, its shape evoking something out of a sci-fi epic. Under the hood hummed an advanced and unprecedented engine. It had to be one of the most, if not the most, futuristic car ever built.

Development of the Cosmo Sport had begun shortly after that of the rotary engine, in 1962. Per Matsuda’s vision to put his company on the map, the groundbreaking Mazda rotary engine would have to debut in a stunning sports car. By the end of that year, the car’s basic layout was settled, with design work underway in early 1963. Mazda certainly chose the grandest of names, fitting for an ambitious vehicle born in the pioneering days of space exploration.

After its surprise appearance at the 1963 Tokyo Motor Show, Matsuda pointed the Cosmo Sport concept southward and personally drove it home to Hiroshima, some 500 miles away. Along the route, he visited Mazda dealers to drum up excitement for the company’s bright future. A Cosmo prototype would be displayed at each of the three subsequent Tokyo Motor Shows as development for the production version continued.

The Cosmo Sport became a testbed for various rotary engine prototypes. In 1965, Mazda built sixty running pre-production Cosmo Sports and sent them to dealers across Japan for real-world testing. Matsuda was behind the program, for which Yamamoto specified three rotary engine configurations across different geographic regions. In all, the test cars gathered approximately 375,000 miles’ worth of data for Yamamoto’s team. At least one of the prototypes still survives in Mazda’s collection in Japan.

The production version of the Cosmo Sport was unveiled at the 1966 Tokyo Motor Show. Its design had undergone some changes compared to the earlier prototype, the most notable being the rear taillights that even better resembled afterburners on a spacecraft. Other minor changes included badging, wheel design, and color scheme. The earlier prototype’s silver roll bar-esque hoop was gone, while the varied colors had given way to white.

The bigger changes were mechanical. The original prototype’s L8A had morphed into a larger 982cc mill, the first member of the 10A family. It was Mazda’s first production rotary engine, with a displacement of 2x491cc and maximum output of 110PS at a stratospheric (for the time) 7000 rpm. Thanks to the compact design of the rotary, it was mounted aft of the front wheels’ centerline, giving the car the superbly-balanced front-midship layout that still underpins modern Mazda sports cars.

Though announced in 1966, the production L10A Cosmo Sport would not go on sale to the public until May 30, 1967. Offered at ¥1.48 million, it cost about forty percent less than the Toyota 2000GT, which debuted just two weeks earlier. Though a relative bargain, it still wasn’t for the masses. The Cosmo was, after all, a halo car, a showcase of cutting-edge technology not just for Mazda, but all the automotive world.

Needless to say, the rotary caught the world’s attention, and Toyo Kogyo would quickly set its sights on American and European markets. Mazda’s grand plan of “rotarization” would soon begin with the mass-market Familia as well.

A Defining Symbol

Like the 2000GT, the Cosmo Sport was a watershed moment. Its arrival declared the technical and engineering prowess of a small but ingenious carmaker from Hiroshima, and, indeed, Japan. It is now one of the most sought after cars to come out of Japan and its cachet only continues to rise.

Through six years of tireless engineering, Yamamoto and his team overcame the immense challenge of bringing to market a fundamentally new type of internal combustion engine, something that most other automakers, many larger than Mazda by magnitudes, could not accomplish.

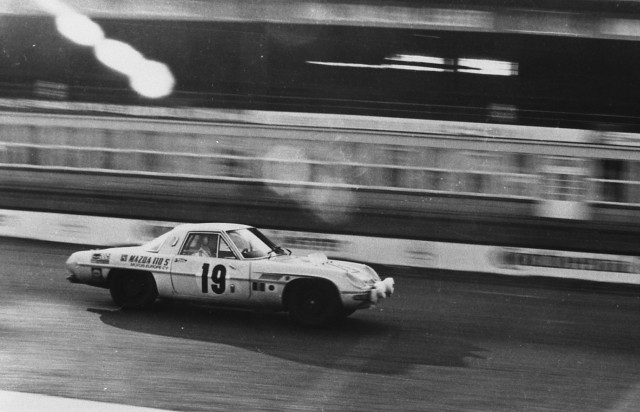

Matsuda’s vision had been realized thanks to Yamamoto and his team’s determination, technical genius, and the tenacious will that only an underdog can sustain. In the years that followed, a flood of rotary-powered Mazdas would grace the world, from family sedans to buses to fire-spitting sports cars. Mazda would even harness its strengths in one of its newfound passions, the crucible of racing.

The rotary would come to symbolize the innovative and never-say-die spirit of the Hiroshima company. Young and talented engineers would be drawn to the company because of it, and numerous novel technological applications would be boldly adopted by Mazda, from electronic four-wheel-steering to the Miller cycle engine to the ultra-high compression Skyactiv engines.

Over the years, Mazda engineers have penned volumes of technical papers about the rotary engine. Through the many changes to the automotive landscape throughout the decades they continued to innovate, making it cleaner, more efficient, and more powerful. They’ve turbocharged it, made one that runs on hydrogen, and won at the highest echelons of motorsport with it. And yet, after half a century, no other automaker has even come close. The rotary belongs to Mazda.

Sadly Mazda has not maintained a successor to the Cosmo Sport or flagship sports car in its lineup since 2012, but despite what you may have heard there remains a small cadre within Mazda, just as dedicated as Yamamoto and his men were, determined to see the rotary engine live again. Even if it never comes to market or is taken in an entirely new direction, one fact stands as a testament to what the Cosmo Sport inspired and the movement it created 50 years ago today — the world still pines for a rotary-powered dream machine.

Images courtesy of Mazda.

Great write up!

Sugoi! Very interesting and informative article Thank You

I personally love the lines of this Mazda over the 2000gt.

Amazing article! Now, how about an article about Nissan’s rotary?

Excellent article, have to admit I certainly love my old Cosmo 110S terrific driving car even by todays standards…

I believe the NSU predates the Mazda car by several years as the first car with a rotary engine.

it does…. but not with a 2 rotor engine.

The NSU Ro80 was a colossal failure that almost brought Volkswagen down.

NSU’s versions of the rotary were indeed failures that ultimately brought the company down. However, it was after (and because of) this that Volkswagen swallowed up NSU.

Puerto Rico love Mazda Rotary, input best power, and technology.. Thank you. INF,50year.excellent.

Unfortunately, it’s unlikely that they’ll be able to make a rotary as efficient as a piston engine.

I would live to see a resurrected RX-3; throw a Renesis in a Mazdaspeed 3.

I didn’t realize that the first rotary motor was released all the way back in 1963.