In a year of momentous anniversaries for Japanese automotive institutions, one stands above all others in shaping the cars we love. Fuji Speedway, which opened in 1966 and turned 50 this year, has been the birthplace of countless legends, whether made of steel or of flesh.

We were honored to have had the opportunity not only to visit Fuji Speedway this year during its year-long 50th anniversary celebration, but to have driven it. Before we get to this once-in-a-lifetime experience, however, let’s start at the beginning.

A Groundbreaking Story

The story of Fuji Speedway begins a bit longer than 50 years ago, when the head of Marubeni Corporation Chohei Mori met with Minister of Construction Ichiro Kono to discuss ways of growing the automobile market in Japan. Kono was, at the time, overseeing the building of Japan’s first expressway, the Meishin, which would catapult Japan into a new age when it opened 1964.

Spurring interest in cars, especially domestic ones, they realized, would require provoking Japan’s carmakers to focus on performance with some healthy competition. The best way to do that? Build a race track.

Soichiro Honda had recently finished construction of Suzuka Circuit, but at the time of its completion in 1962 Honda yet to build its first car. It was thought that Suzuka was designed for motorcycles, and that a high-banked track wide enough to run several cars wide was needed to see proper doorhandle-to-doorhandle action.

For inspiration, they looked to an unexpected muse — Daytona, the roots of American motorsports and pre-saltflat international mecca for anyone yearning to set a land speed record. In 1959, NASCAR opened Daytona International Speedway to give a formal home to the races taking place on the Florida coast.

A deal was struck with the American sanctioning body and the Japan NASCAR Company was founded in 1963. Among the early investors were Marubeni, the Mainichi Shimbun newspaper group, and the Fuji Kyuko Company, a train car manufacturer which just happened to operate two rail lines taking tourists from Tokyo to Mt Fuji.

A parcel of forested land at beneath Japan’s most famous peak was chosen. Soon, it would be hosting a series of NASCAR-style races in which Japan’s carmakers would vie for supremacy in the grand tradition of America’s Ford-GM-Mopar rivalries. Or so it seemed.

Construction began on a towering 30-degree gradient, but after just one of four such bankings was finished, the project stalled. Many reasons have been offered as to why, including the unexpected expense of erecting a huge, expansive oval over the rugged foothills of Mt Fuji.

Given the terrain, it was decided that the best course of action would be to build a circuit-style road course incorporating what already existed of the banked section. The revision meant dissolving the NASCAR contract and its pricey licensing fees, and ending hopes of a decades-long horsepower war with big Japanese sedans. Crown versus Cedric stock car battles did surface here and there, but it would never become the full NASCAR spectacle enjoyed in the States.

By 1965 the company was renamed the Fuji Speedway Corporation, retaining the word “speedway” despite the fact that it technically no longer was one. Mitsubishi Estates, part of the Mitsubishi zaibatsu, took over management and finished the construction. Sadly, Kono passed away that same year, never to see what his undertaking would become. His son, Yohei, who for a few years oversaw development, coined the nickname FISCO, for Fuji International Speedway Company. Even today, old schoolers still call it by that name.

Built for Speed

Fuji may not have been a speedway, strictly speaking, but speed would nevertheless become its defining trait. A mile-long straight through the viewing area fed directly into the old NASCAR bank, which eventually earned the nickname Daiichi, or “Big One”. From there, the track consisted of a series of wide sweepers — a sharp contrast against the tight hairpins of Suzuka — and Fuji became instantly known as one of the fastest road courses on the planet.

Unlike every other speedway in the world — which saw banked sections rise up from the straights that led into them, designed to slingshot cars around the bend — Fuji’s opened downward, at the end of a blind crest no less, to cars carrying speeds in the high triple digits. In time, Fuji would come to be known as one of the world’s deadliest circuits as well.

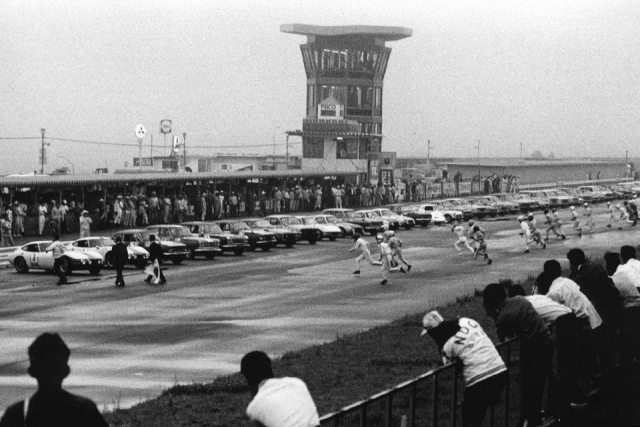

Fuji Speedway held its first event, the 7th All-Japan Motorcycle Clubman Race, on January 3, 1966. Despite the fact that the field consisted of amateur riders and that some seating areas were still under construction, 10,000 people showed up.

In May, it hosted the 1966 Japan Grand Prix, stealing the headline event from Suzuka. The highlight of the race was Toyota’s race-modified 2000GTs going head-to-head against the eventual winner, Prince’s purpose-built R380s, while Nissan Fairlady roadsters, Jaguar E-Types and even a Shelby Daytona Coupe mixed it up in the field. This time, the crowd was 95,000 strong.

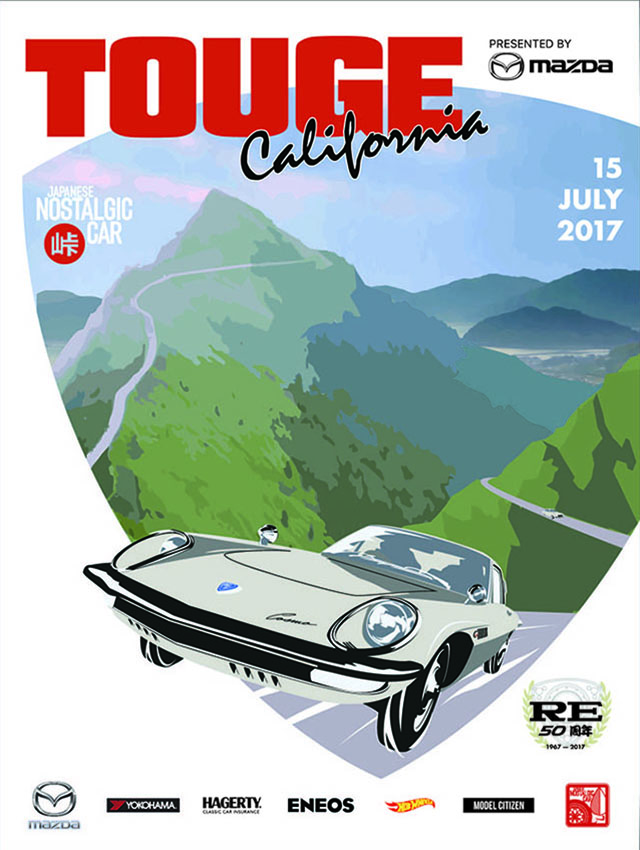

Soon, Japan would enter a golden age of motoring. 1967 saw the birth of cars like the Toyota 2000GT, Mazda Cosmo Sports, and Nissan Fairlady 2000. That year, Japan became home to the world’s third 24-hour endurance race (after Le Mans and Daytona) with the 24 Hours of Fuji. Run in conditions of thick fog — a recurring theme that Fuji would become notorious for — it ended with a thrilling photo finish of two Toyota 2000GTs sandwiching a lapped Sports 800, an image used as Toyota PR for decades.

A landmark occasion in Japanese automotive history took place at Fuji Speedway on May 3, 1969 at the JAF Grand Prix. It was at this race that Nissan’s unleashed the Skyline GT-R unto the world. It was still the PGC10 sedan version, earning it the nickname Hakosuka (or “box Skyline”), but its Prince-developed racing engine helped it win its class, Touring Sedan B, on its maiden voyage and created a legend.

By October of the same year, the Hako had won its seventh victory, at the Japan Grand Prix also held at FISCO. For the next two years, the Skyline GT-R would dominate Japanese touring car racing, building a record of 49 victories (29 of which were consecutive by Nissan’s official works team). And then, when Nissan’s confidently predicted 50th win was cruelly snatched away by Mazda’s Savanna RX-3 in a dramatic rain-soaked battle straight from the movies, well, that happened at Fuji Speedway too.

Meanwhile, at the highest echelons of Japanese racing, Nissan and Toyota were duking it out with cars like the purpose-built R382 and Toyota 7. The hope was that eventually the cars would compete internationally in Group 7 series like CanAm, but by the end of the 1960s they were so powerful that they had to run counter-clockwise to protect drivers from Daiichi. According to Vic Elford, who was trying to get Nissan and Toyota come to the US to race in CanAm, it got so dangerous that Group 7 cars had to be banned altogether in Japan.

Cornerstone of Car Culture

With rival giants Toyota and Nissan out of the purpose-built racer game, FISCO came up with a new series. On April 25, 1971, the inaugural Fuji Grand Champion race took place. Thus began the era of independent chassis-builders like Moon Craft, Chevron, and March running single-seaters powered by small displacement engines like the Mazda 13B, Toyota 18R-G, Mitsubishi R39B, BMW M12 and Cosworth DFV.

Ostensibly, these were the headline act, but what really came to define the Gurachan (or Grachan, short for Grand Champion) era were the supporting races. There, cars like the Toyota TE27 and turbo Celica, Mazda Capella RX-2 and Savanna RX-3, Nissan Fairlady Z and Sunny — cars that aspiring car enthusiasts could actually buy — duked it out for the hearts and minds of budding petrolheads across Japan.

Fans would drive hundreds of miles to watch the races, filling the FISCO parking lot with arrays of J-tin that would drop a JCCS attendee’s jaw to the floor. It became a lifestyle, and along with the touring car races of the time, forged a passion that spawned all the cars and tuning culture that we enjoy today.

Sadly, a run of horrific accidents claimed the lives of Fuji GC racers Masaharu Nakano, Hiroshi Kazato and Seiichi Suzuki in late 1973 and early 1974. As a result, FISCO finally decided to redraw the track, bypassing Daiichi and creating the first of Fuji’s famous hairpins at the end of the straight. The old banking was left to deteriorate and its remnants still exist in present day.

For most of the world’s car enthusiasts, Fuji Speedway barely registers a blip on the radar. It’s known mainly for one thing — the stunning victory of James Hunt over rival Niki Lauda in the final round of the 1976 Formula One season. It was the first year Japan would appear on the F1 circuit. The success was short lived, though, because 1977 another accident sent Gilles Villeneuve flying into a crowd of photographers and marshals, killing two.

Formula One would not return to Japan until 1987. Once again, the world mostly forgot about Fuji, but domestically its popularity only grew. The Grand Champion series continued and in 1979 adopted the Group 5 Silhouette formula, giving rise to monstrously flared and be-winged examples of the Nissan DR30 Skyline, Silvia, and Bluebird, as well as the Toyota Celica, Mazda RX-7, Porsche 935 and BMW 3.5CSL. This was the era that fathered what came to be known as the bosozoku style of modification, characterized by exaggerated aero parts and reckless street antics.

Evolving with the Times

As a result, some residents around Fuji Speedway began a petition trying to convince the government to shut it down. The noisy and risky driving behavior of Grachan fans hooning their way into and out of FISCO was cited as a main reason. It was believed that motorsports promoted dangerous driving on public roads. The 1983 death of up-and-coming 23-year-old driver Toru Takahashi at Fuji didn’t help things either.

In response, a team of drivers, racing journalists, and residents who supported FISCO launched a countersuit. Some say that legendary Hakosuka GT-R Works driver Kunimitsu Takahashi even organized a march in support of the circuit. After a hard-fought legal battle, courts ruled in 1986 that the Speedway could stay. F1 returned to Japan the following year, but would call Suzuka its home for the next two decades.

The Fuji GC series ended in 1989, giving way to the growing popularity of the All-Japan Touring Car Championships (JTCC) and Group A racing, held at Fuji but also numerous other circuits across Japan. This period gave rise to cars like the Toyota AE86, Honda Civic, and R32 Nissan Skyline GT-R, but the age of Fuji’s dominance on Japan’s motorsports scene was over.

Fuji continued to host all manner of racing series, from Super Taikyu to the NSX-Supra-Skyline GT-R battles of JGTC to the 21st century sport of sanctioned drifting. By the late 90s, Fuji Speedway had fallen into disrepair. Toyota took over management of the track in 2000, revamping facilities and redesigning the course to its current layout in 2004.

On Hallowed Ground

Back in June, I was invited by Subaru to drive the 2017 BRZ at none other than FISCO itself. We had been to Fuji Speedway before, but to actually drive it — that was an item I didn’t even know was on my bucket list because it seemed like such a pipe dream.

On the morning of the drive, nine other journalists and I piled into a bus at 6am to beat rush hour traffic out of our hotel at the Toranomon Hills area of central Tokyo. Jetlagged and bleary-eyed, most were quiet for the ride, but I was overcome with emotions I hadn’t felt since childhood on a Christmas morning.

Tokyo sprawl gave way to thatched-roof farmhouses straight out of Seven Samurai, and about 90 minutes later we exited the expressway to begin our climb to Oyama, population 20,000. The small town is almost indistinguishable from thousands of others across rural Japan, with ramen joints, bicycle shops, and kombini lining narrow streets. You can understand why residents of the quiet town wanted to shut the track down.

It always rains at Fuji Speedway. Despite sunny weather in Tokyo and along the entire route through Shizuoka Prefecture, as soon as we crossed FISCO’s gates we were among clouds. Nestled between the Tanzawa Mountains and Mt Fuji, it’s the perfect geographical condition to trap precipitation during Japan’s tropically humid summers.

After a presentation about the merits of the refreshed BRZ from Subaru’s engineers and designers, we were shuttled to the short course. Like many circuits, Fuji has many smaller paved areas for various automotive activities: a lineup of uniformed patrolmen in Toyota Crowns in preparing for a police exercise, SuperGT team trailers, and some kind of an autocross consisting entirely of JZA80 Supras.

At the short course, we were thrown the keys to BRZs for driving impressions. The car handled great, a bit softer than the zenki version, and had a dab more horsepower. Mostly, though, all I could think about was the fact that the Daiichi banking was looming right behind us like some ghostly ancient monument lurking in the mist.

Thirty degrees of banking doesn’t sound like much, but in person it’s a freaking wall. It scrambles the mind to imagine fearless racing heroes charging into the basin on bias-ply tires and nothing but the most rudimentary safety gear.

The facelifted BRZ is handsomer than the version it replaces and the boy-racerish Toyota 86. If you get the Performance Package, included with improved brakes and dampers are a set of 17-inch wheels that were inspired by the very RS-Watanabe racing wheels that used to carry racing Hakos at speed across this very spot. I asked designer Yuki Komono if he was inspired by the racers of old. “Yes,” he replied, “But it’s a secret.”

Lunch was served in rooms above the Subaru paddocks. As we dined on soup and what I think was saba, practicing SuperGT cars — the Calsonic GT-R, Raybrig NSX and Zent Lexus — roared down the straight. The soaring Fuji grandstands are famous for echoing the exhaust notes of charging cars, and the sounds reverberating from these state-of-the-art machines were downright ethereal.

Finally, it was our turn. But by late afternoon, a fog thicker than the miso at lunch had rolled in, reducing visibility to about two car lengths. Fuji in its current iteration is a very technical course, with multiple confounding late apexes and off-camber turns. Even having “driven” it a couple of times in Gran Turismo, I felt like I was going in blind.

By the end of the straight, even a stock BRZ can hit 130 mph. And with nothing but a wall of fog in your windshield, you really have to be generous with the brakes to avoid the somewhat undesirable technical condition known as an “off”. How fast I dared to go was limited to some combination of the following: not being familiar with the course, wet tarmac, shifting with my left hand, not wanting to destroy a brand new sports car in front of its makers, general cowardice, and having as much visibility as being inside a cardboard box.

Still, I was driving over the same hallowed ground where Gan-san, Wolf Kitano, and Masahiro Hasemi made their names. It was these daredevil exploits that captured the imagination of Japan in its motoring youth. They risked life and limb beneath the mystical Mt Fuji while Shinto’s ancient gods bore witness to these men, writing history in chariots of Japan’s own making.

Many titans of the Japanese auto industry remember those days. A direct line can be traced from FISCO’s heyday to Japan’s current carmakers, and the glory years very much shaped the minds of gearheads of that would become the tuners, racers, and engineers at the shops, circuits and marques we adore today.

I drove on that land, and I will never forget that.

Images courtesy of Fuji Speedway, Subaru, Nissan.

SWEET!

I really like the shots you captured with the old bank in the background – relative to the foreground you begin to appreciate just how extreme it is.

Thanks! It was really amazing in real life. At first I thought it was a wall!

Awesome story guys!!!!!! 🙂

Japan’s most legendary track, set at the foot of Japan’s most sacred & legendary natural giant.

To actually drive it, even slowly, would be beyond words. So very, very, very, very lucky!

They say you should not “meet” your heroes, reality & truth being at odds with what is built-up in your mind.

But, there could be no way that a Fuji experience would ever let you down.

A similar story about Tsukuba (if already not done) would be appreciated & a great article too……………

Thanks, Michael! Among all the stories I’ve had the privilege to write, this was a top 3. Being there and driving it was like, for me, worshipping at an old cathedral. It’s an experience I’ll cherish forever.

Thanks for great article! I love the history and your article clearly explained F1’s absence so well.

Wow, 30 degrees. That’s about the standard bank angle for an aircraft at 1.2 G’s.

Fuji Speedway is on my want list to visit, but by train, it doesn’t look easy. Weird, since one of the founders was from a railway company. Thanks again for the great article!!!

Forget the train – hiring a car and driving to Fuji Speedway really is easy. These days you can hire cars with English GPS, plus armed with a Smart Phone, you can’t go wrong. You’ll see some really cool stuff driving around, too.

From Wikipedia:

Vic Elford recalls:

“In 1969 I spent two months in Japan doing a test contract for Toyota and their Toyota 7 (5 litre V-8), which along with a big Nissan (6.3 litre V-12), was destined for CanAm. My last testing and then the subsequent Sports Car GP were at Fuji, but the track was run in a clockwise direction. The reason that banking was so horrific, was that at the end of the straight we went over a blind crest at around 190/200 mph and dropped into the banking. At other tracks (Daytona, Monthlery, etc.) you climb up the banking. One of the results was that although there were many brave Japanese drivers there were not too many with great skill and the death toll from that one corner was horrendous. To such an extent that the big Gp 7 cars were then banned in Japan and thus, neither Nissan or Toyota ever made it to CanAm.”

It’s a shame the Toyota 7 and Nissan R382 never made it to Can Am racing in the US. I’d have loved to see the ,never raced, R383 with a 6L V12 turbo taking on the Porsche 917/30.

One of these days I’ll have to drive the old Fuji circuit in the racing sim, Grand Prix Legends.

Thanks for the story about Fuji Speedway.

Many thanks to Ben and the JNC team for this and so many great articles throughout the year. You get a sense of the impact FISCO has had on racing history in Japan just by looking at how the article was tagged. Really enjoyed the write-up and pics. I am admittedly not well versed in the different racing series, but Group 5 has always stood out to me. In my favorite episode of Seibu Keisatsu (104), it is loaded with Japanese auto goodness, including scenes at FISCO with a Group 5 Gazelle. This one will be hard to top, but looking forward to 2017!

Thanks, John! Much appreciated, and cheers to your witty comments!

hi, anyone know what kind of car is this? protagonist car from manga HOMUNCULUS.

mangafox.me/manga/homunculus/v05/c000.1/94.html

Awesome story Ben. I remember the coverage from BMI when the circuit was closed in 2004.

You are very lucky to have been on the circuit.

This inspires an even higher respect for the forefathers/history of Japanese motorsport that paved the way to 90s legends that are my childhood, awesome article. Thank you.

Yeah, surprisingly little has been written about Fuji Speedway in English, especially in a way that connects all the threads. Glad you enjoyed it!

Hi Ben/ This is memories for me. Having been to Fuji and travelled only in the bus, was incredable. I was also fortunate to see the ZamaCollection at Yokohama before it was split up. Having owned Prince Skyline S54B’s – Datsun Bluebird SSS – Isuzu 117 Coupe’s since 1966. This story really is briliant. Back to Zama, to see those vehicles race cars and also the evolution vehicles. Wow. I spent, 4 hours walking around with the S20 club. Sitting in the R380 Race car, standing with R380.1 etc, I could keep going for ever> I took photos and video which I treasure. Probably the moment for me was seeing # 73 Kenmari in flesh and stated up, along with,the #39 Prince Skyline, as well as the # 39 Gloria especially seeing a prince ALB1 unveiled (RED) which had 1 mile on it. It was the 2nd car built. Thanks for your story. I loved it and all the photos etc.

Thanks for the kind words and trip down memory lane, Ray. You’ve had some nice cars in your day. Thank you for reading!

Hi ! superb report on Fuji best years when it was Grand Champion and Long Distance Series from 1971 to 1978 and after…

I am searching for photos of Japanese issues like Auto Technic 76-1 about GC 71 to 75 races and other reports on 1975 to 1978 GC and LD events.

Let me have the privilege to receive your participations to my quest for those magical photos, i let my email here to You : mosleylucky at yahoo.fr

Thank You very much to answer to my demand and do not hesitate to ask me for European photos of the raced events and Japanese cars here in France like Le Mans 24 hrs. Cheers !

you forgot 1972 to 1978 GC / LD PERIOD !

ALL JAPANESE BEST DRIVERS OPPOSED TO FEW EUROPEAN ONES COME TO COMPET WITH THEM… THE BETTER SHOW OF THE GRAND CHAMPION SERIES.

HELLO, don’t You forget samples of the famous Fuji Grand Champion & Long Distances Series from 1975 to 1979 ? They were the best ones.

GRD, LOLA, CHEVRON, MARCH, ALPINE HARADA, TOYOTA, and many confidential Japanese beautiful cars like MOONCRAFT’S…

Let us discover the Automotive treasures of Japan in other pics and documents, thanks !