Twenty-five years ago today, the Mazda 787B started on a 24-hour journey that would change Japan’s motorsport history. As you know, Mazda won the 1991 24 Hours of Le Mans, and in parts 01, 02, and 03 of our tribute to this car, we provided you the historical facts of the journey that led to this victory. Now, let us put that journey into perspective and take a look at the implication and influence it has on some of our favorite JNCs.

If you made it through all three previous parts of this series, you should be struck by how long the Mazdaspeed team grappled with the Le Mans challenge. Le Mans is a tough race. Sure, Mazda had competed in the Marathon de la Route — aka 84 Hours of Nüburgring — and finished the race on its first attempt with its first-ever rotary vehicle, but Le Mans is still tougher in many ways.

An overall Le Mans victory is achieved only with a purpose-built, ultra-high-speed race car. That means complexity and cutting-edge engineering that always pushes the envelope and that must also be efficient and reliable, all developed within tight timeframes. As Toyota proved last weekend, the number of things that can go wrong is staggering.

And it was the overall victory that the Mazdaspeed team and Mazda went after; class wins alone were not good enough. In 1973 when Takayoshi Ohashi, then Racing Manager at Mazda Sports Corner, conferred with Shin Kato of Sigma Automotive, their objective was to put Japan on the international racing map.

This was the reason they chose Le Mans, as its history, renown, and difficulty makes it impactful. The incredible part of the story is that over a span of roughly eighteen years, they never took their eyes off the prize. Losses and disappointments littered the road, even right up to the 787’s performance in 1990, but they were never defeated. Without fail, the Mazdaspeed team always dusted themselves off and faced up to the challenge.

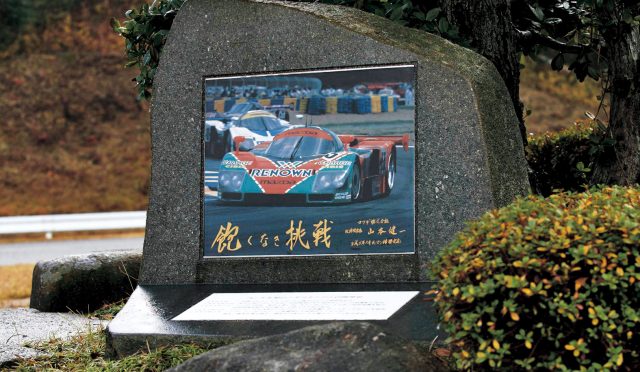

In fact, this has become a creed of sorts for Mazda: Never stop challenging. After the ’91 Le Mans victory, Kenichi Yamamoto — the famed rotary engineer and then chairman of Mazda Motor Corporation — ordered a plaque installed at Mazda’s Miyoshi Proving Ground commemorating the #55 787B, along with the words “Never Stop Challenging.” The same spirit enabled Mazda’s “47 samurai” to bring the rotary engine to reality; on the Le Mans front, it gave a movie script ending to the Mazdaspeed team.

Something else that might have struck you from our recount of this Le Mans odyssey are the names of people that you might be familiar with. Takaharu “Koby” Kobayakawa is a household name among RX-7 fans, having been the Program Manager of the FD3S development.

Koby-san also oversaw the development of the FC3S after launch and was responsible for the FC convertible as well as the Series 5 and Infini models. Incidentally, during development of the FC convertible, he invented the windblocker now so ubiquitous among open-top cars. Koby was also one of the 47 samurai and helped develop the racing engine for the Marathon de la Route Cosmo Sport. As Mazda’s racing Program Manager from 1990 on, his used his expertise to push for performance targets and availed company resources to the Mazdaspeed team in order to reach those targets.

You might have also heard of Takao Kijima, who at the time was Koby’s chassis engineer on the FD3S team. Kijima would go on to take over the reins of FD’s development. If you are a fan of FD’s evolution models, such as the Type RZ, Type RS, or the ultimate Spirit R versions, Kijima is the one to thank. Kijima also oversaw development of the NB and NC MX-5 Miata. He is as much a sports car tour de force as Koby-san, and his work on the 787B’s chassis development was absolutely essential to the victory.

To drop one more name, there’s Nobuhiro Yamamoto. Yamamoto was one of the first engineers at Mazda to work full-time on the racing rotary engines, appropriate as he was a proponent within the company to develop and improve the rotary engine through racing. He worked on 787B’s R26B 4-rotor as well. Yamamoto would later become Program Manger of the ND MX-5 Miata, a car that defies modern sports car conventions to stay true to the spirit of the pure sports car.

The point here is that many of the people who participated in the Le Mans effort were also directly responsible for Mazda’s road cars. And it wasn’t just the engineers; Yasuo Tatsutomi, who gave the 100hp increase edict for what would become the 1990 R26B, was an executive officer of product planning.

The race program at Mazda has had a direct trickle-down effect to the likes of the FD and ND. Racing is often justified as a device for marketing and technology development. In this case, it is also a reflection of the culture and enthusiasm of the Mazda people.

Mazda is of course also celebrating the 25th anniversary of the 787B’s win. They’ve re-wrapped refinished the #55 Prototype that currently races in the IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship in the 787B’s iconic orange-and-green livery, as shown in the lead photo. It will be raced throughout the 2016 season. But we at JNC also have something in store to commemorate the occasion. Stay tuned.

That concludes our retrospective on the 25th anniversary of the Mazda 787B’s historic win at Le Mans, but in case you missed it here’s Part 01, Part 02, and Part 03.

Images courtesy of Mazda.

Fantastic piece… what a great piece of history and what a great read…

I was lucky enough to see and hear the 787B at Goodwood last year. The sound is amazing, even at idle the rapid, barking braps sound like an overgrown puppy, somehow combining the eagerness of youth with the basso profundo of a fully grown canine. The styling is also awesome, like all that era’s Group C cars, like a roadgoing supercar evolved for competition.

If you want even more details than this blowout JNC coverage, the gigantic hardback book “Never Stop Challenging” by Pierre Dieudonne seems decent value at £40 – https://www.amazon.co.uk/Never-Stop-Challenging-Mazdas-Conquest/dp/2930354569 – it’s packed with engrossing period photos, as well as telling the full, year by year story.

The optimistic, never-give-up spirit of the Le Mans programme is definitely reflected in the FD3S, the confidence to go for novel engineering solutions; the rotary, the sequential turbos, the complex venting, the sweep of the doors, the powerplant frame linking gearbox to diff, and so on. The car feels race-bred, with transparent, instant responses, the whole car moving as one, so easy and natural to drive fast.

Mazda’s Le Mans programme is a great example of technical vision, determination, and guts. Its gradual rise, final triumph, and subsequent retirement perfectly exemplifies the rise of the Japanese car industry from post-war ashes to early-nineties peak. And those not fortunate enough to get to drive the 787B up the Goodwood hill, the FD3S remains the best roadgoing embodiment of that ingenious, indomitable spirit.

Speaking of Mazda victories at Le Mans, let’s not forget the Group C2 class win in 1984 by the Mazda-powered BFGoodrich Lola 616.