In the previous installments of our 25th anniversary commemoration of Mazda 787B’s historic Le Mans win, we looked at the race car’s genealogy as well as the origin of its team. With the rules change imminent, it was the last year a non-piston engine would be permitted. It was Mazda’s final rotary assault at Le Mans.

The 787

For 1990, Mazda had prepared its ultimate Le Mans powerplant, the R26B. The car mated to this engine, again designed by Nigel Stroud, was the extremely advanced 787. Unlike its predecessors, it now had a monocoque chassis made of carbon composites, with longer wheelbase for stability and reduced front track to increase top speed. Other improvements included improved aerodynamics and relocation of the radiator to improve weight distribution. It was thought at this time that 1990 would be the final chance for Mazda to bring home an overall Le Mans victory, as upcoming FISA regulations were to transition cars to using 3.5L Formula 1 engines.

However, this year was not to be. During testing at Estoril Circuit in April, the 787 showed great performance, although it was glitchy and could not finish the targeted test distance. At Le Mans, neither of the 787s crossed the finish line, while the 767B finished 12th place. A crushing result. But typical of Mazda, they picked themselves up and went straight into problem-solving to overcome the challenge. In the debriefing at Mazdaspeed’s Tokyo headquarters, the team identified 220 points for improvement that would go into the making of their next car.

Mazda’s Ultimate Sports Prototype Evolution: 787B

The Mazdaspeed team, which now included many from Mazda in Hiroshima, immediately began preparing for the next season. Through computer simulations, something Mazda had used in motorsport applications since the 60s, racing program manager Takaharu “Koby” Kobayakawa determined that the car had to run seven seconds quicker per lap while maintaining its current fuel efficiency.

To achieve this, Koby-san brought on Takao Kijima from his team that engineered the chassis of the FD RX-7. Kijima used extensive computer simulations, but his team had to quickly develop the mathematic models for the carbon monocoque from scratch, as none had previously existed! The results helped the engineers make crucial modifications to improve the car’s rigidity. In addition, the team also made the decision to switch to carbon brake discs — the first application at Le Mans.

On the engine side, rotary engineer Yoshinori Honiden looked into upping reliability, as one of the 1990 787s actually suffered an engine failure. They discovered that the ceramic coating in the engine housing was not uniformly sprayed and corrected that. They also switched the ceramic apex seal to a 2-piece design—something Nobuhiro Yamamoto had learned from his experience developing the FD RX-7’s 13B-REW. In addition, the induction system now had a continuously variable intake manifold, providing a wider power band and increased mid-range torque.

As to the question of eligibility and regulations, manager Takayoshi Ohashi worked hard on the diplomacy and politics side to enable the rotary Mazda to race one more year. Fortunately, the new 3.5L engine regulation was not well-received by many teams and manufacturers, and the number of cars entered for 1991 were initially low. FISA thus allowed the older cars to remain in “Category 2” while the new 3.5L cars were in “Category 1,” viewing sprint-type races as the future for its World Sportscar Championship.

Following the heartbreaking 1990 Le Mans race, Koby-san and Honiden decided to bring on six-time Le Mans winner Jacky Ickx as a consultant. Ickx advised that full 24-hour pre-race testing was absolutely necessary. Koby thus planned two such testings of the 787B at Circuit Paul Ricard in France for February and April of 1991. Unfortunately, the team was barred from traveling to the first one in February due to outbreak of the Gulf War. Instead, scattered tests were conducted in Japan. Following the full test in April, however, the team was confident and felt very well-prepared.

1991 24 Hours of Le Mans

This was it. The last year with the rotary — Mazda’s proud, signature technical achievement — at Le Mans. As per tradition, the Mazdaspeed team began their week there with dinner at the Ibis Est Hotel on Monday evening. During the week, there would be scrutineering of the cars, practice sessions, qualifying, and parade.

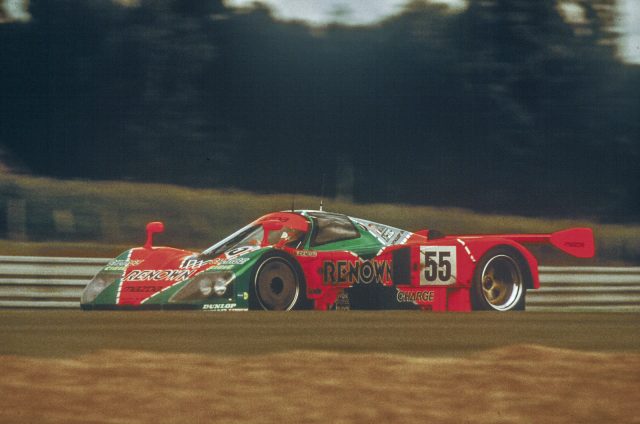

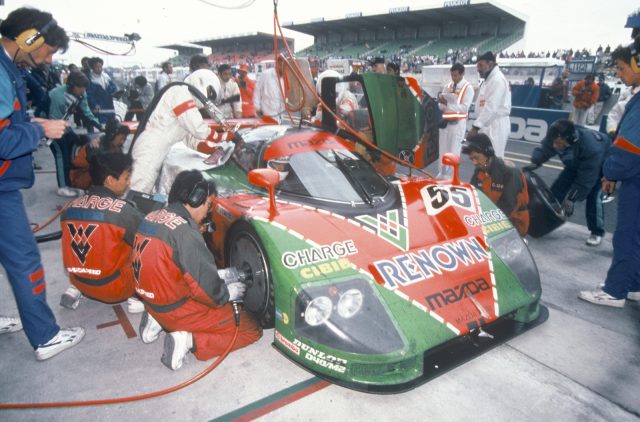

Mazda again fielded three cars at Le Mans that year: #56 787 driven by Terada, Yorino, and Dieudonné; #18 787B driven by David Kennedy, Stefan Johansson, and Murizio Sandro Sala; and #55 787B driven by Volker Weidler, Johnny Herbert, Bertrand Gachot. The last three were new drivers from Formula 1, brought on because Ohashi decided in 1990 to began training young drivers for the Mazdaspeed team. Three experienced Mazda drivers — Terada, Yorino, and Dieudonné — were placed in the 787 to absolutely ensure that at least one car crossed the finish line. Though Mazda was not favored to win, the crowd loved the rotary prototypes for the distinctive sound of the 4-rotor.

During testing, the 787B had been shown to be reliable. The #55 car in the orange-and-green Renown/CHARGE livery was thus ordered to push hard within the fuel consumption limit — fitting as it was piloted by the three F1 youngsters.

Early in the race, the three Sauber Mercedes-Benz C11s quickly took the lead, while the Porsche 962Cs and Jaguar XJR-12s struggled to balance speed and fuel efficiency. The comparatively lightweight 787B, in contrast, was running in a consistent pace, and after a quarter of the race, #55 was already fighting for fourth place with the #35 Jaguar and #57 Porsche.

The Porsche would retire by the end of the night, and by half race distance, #55 was in third place and #18, eighth. The #56 787 was slower, but all three cars were running strong. One of the Sauber Mercedes-Benzes (whose drivers included one Michael Schumacher) then suffered transmission problems, and #55 moved into second place.

At this point, the Mazdaspeed team was starting to hold its breath as victory was tangibly possible. The outlook, however, was that the Mercedes was likely to maintain position and win. It now really came down to a question of reliability.

Then, with about two hours left in the race, the lead Mercedes went into the pits! Eleven minutes later, the #55 787B took the lead of the race to an eruption of crowd cheers. The elation of the Mazdaspeed team, which has always had a tradition of familial and friendly atmosphere, must have been unimaginable.

With the Benz in the pits, the leading #55 diligently worked to build up the lead. The Mercedes went back into the race sixteen minutes later, only to run one more lap before retiring. The Jaguar still posed a threat, but the orange-and-green 787B ran like clockwork, pitted one more time with just enough fuel added, and took the checkered flag.

Unbreakable

After Le Mans in 1991, Koby ordered the winning #55 787B shipped back to Japan uncleaned and untouched. It was taken to Mazda’s R&D center in Yokohama where, in full documentation by a group of technical journalists, the R26B was removed and disassembled. The inside of the engine was as new, with little evidence of wear. The four-rotor engine was unbreakable.

As was the Mazdaspeed team. The win was the culmination of efforts and perseverance stretching back to the 1970s, and it was a win for all team members, drivers and engineers involved. It was an amazing achievement and odyssey by a group of people who refused to be beat and who was determined to overcome an incredible challenge. And they did it with panache, too: in a wild orange-and-green car spitting fire from its sides and screaming like no other engine could in the last year of their eligibility. It doesn’t get any better than this, even after twenty five years.

The #55 Le Mans winner now resides in Mazda’s museum in Hiroshima. A replica of it also can be found in the Musée Automobile De La Sarthe at Le Mans. We hope you enjoyed this recount of Mazda’s Le Mans journey. It should be said that the words here provide but a bird’s eye view. Comprehensively, the people and stories involved can fill volumes. Perhaps for another day.

To be continued…

We’ll have more on the 25th anniversary of the Mazda 787B’s historic win at Le Mans, but in case you missed it here’s Part 01 and Part 02.

Photos courtesy of Mazda.

Thank you for this great read. The sound of the rotary prototypes, especially the 787B, is amazing.

This lifts my spirit a bit, which was crushed earlier today when Toyota’s TS050, all but assured to win the 24 Hours with its dominant drive this year, failed on the very last lap, handing the victory to Porsche. Adding insult to injury, the car didn’t get going in time to cross the finish line within six minutes of the winner, so it was a DNF, denying at least a 2-3 podium for The Big T. It’s as if Toyota is cursed, given all its strong finishes at ale Mans that weren’t quite enough over the years, a shadow hanging over a company that has made numerous great prototype sports cars and fielded its share of respectable teams at Le Mans.

Despite a rich history in sports car racing’s prototype classes, including being an engine supplier for many successful class 2 prototypes (P2), Nissan has never won the great French race outright, either.

Only Mazda! I had the pleasure of hearing a 787B in person at a historics event at Road America a number of years back. That noise! That glorious noise! Eargasm!

What a brilliant read! I get goose bumps reading this story, It really would make a great movie.

A great story and a cliff hangar end (even though we all knew the outcome).

For more details on the R26B:

http://www.rotaryeng.net/Mazda_R26B_US.pdf

“They also switched the ceramic apex seal to a 2-piece design—something Nobuhiro Yamamoto had learned from his experience developing the FD RX-7’s 13B-REW.”

Can anyone clarify this? Jack Yamaguchi’s FD book shows the 13B-REW having 3 piece seals.

The apex seals in the FD’s engine does use a 3-piece design. The 2-piece (vs. 1-piece) design referred to here in the race engine was new and, curiously, something learned from Mazda’s production car development.

Of course, rotary engine in the production cars didn’t use ceramic for their apex seals; they were cast iron.

Hi j_tso, thanks for that PDF. I can never tire of reading about the 787B or the R26B engine.