The 2016 24 Hours of Le Mans is now underway — a perfect occasion to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the historic victory of the Mazda 787B. If you’re listening to or watching the race live, join us on a break for a glimpse into Mazda’s Le Mans odyssey.

In the previous installment, we looked at the origin and initial experience of the team that would campaign Mazda rotaries at Le Mans. We pick up the story after its fourth outing.

Enter Mazdaspeed

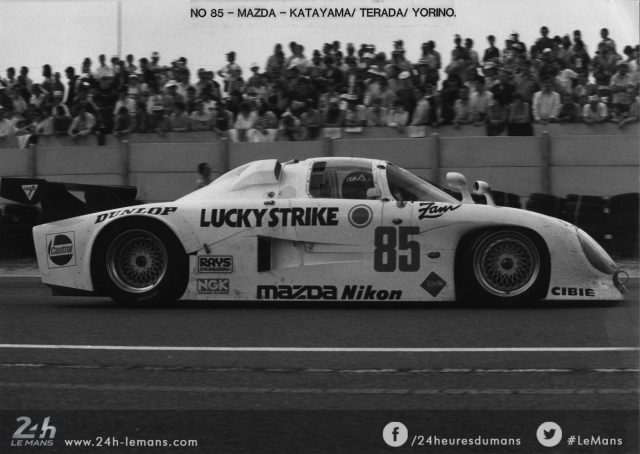

In 1982, Mazda Sports Corner evolved into Mazdaspeed, Co. Ltd, an independent racing organization. Still based in Tokyo and managed by Takayoshi Ohashi, Mazda was now the team’s majority shareholder. Mazdaspeed continued at Le Mans with the 254i. Encouragingly, one of the cars — the one piloted by Yojiro Terada, Takashi Yorino, and Allan Moffat — finished 14th.

1982 was also important in that FISA, the regulatory body, introduced the new Group C class which included fuel consumption regulation as well as an economical Group C Junior class. This opened the door for Mazdaspeed to develop its first dedicated sports prototype.

Up until this point, Mazda’s Le Mans entrants were based on first generation RX-7s with aerodynamic modifications designed by Mooncraft, a race car constructor based near Fuji Speedway. In 1982, Mazdaspeed commissioned from them a Group C Junior prototype racer.

Designed by Mooncraft chief Takuya Yura the resultant 717C was constructed entirely in Japan by Mooncraft and its subcontractors. It continued with 13B power but was compact and very low drag, aerodynamically speaking. At its Le Mans debut in 1983, it took 12th and 18th overall and were the only cars in its their class to finish. Subsequent evolutions — 727C and 737C — would address its glaring flaw: lack of downforce and terrifying manners on the Mulsanne Straight.

Around this time, however, it was clear that more power was needed. Toyota and Nissan had entered Le Mans with turbocharging and, later, V6 power. Mazda thus began exploring avenues to increase horses, a fascinating chapter of which was a twin-turbo 13B powering a March 84G that Mazdaspeed entered in the 1984 Fuji 1000km as an experiment. It was driven by Mazda legends Yoshimi Katayama and Yorino, but sadly technical problems with the turbocharger and poor fuel economy ended further development. What was Mazda to do in terms of power?

Multi-Rotor Begins With Secret 3-Rotor

Thanks to Ohashi and Terada’s diplomacy and connections, Mazda itself was always involved with Mazda Auto Tokyo’s Le Mans challenge, largely on the powertrain side. Still, by the early 1980s, only two Mazda engineers in Hiroshima — Nobuhiro Yamamoto and Junichi Funamoto — worked full-time on racing engines. Along with their boss Noriyuki Kurio, the engineers concluded that the solution to the power problem lies in 3-rotor engines. However, with technical challenges and no company approval, they were forced to work on the 3-rotor in secret during off hours.

Fortunately, the official green light came in 1983, leading to the first version of the 3-rotor race engine: the 13G. It put out 450hp at 9000rpm, 150hp more than the 737C’s 2-rotor 13B. With this new powerplant, a new car was needed for the next generation of Mazda’s prototype racer.

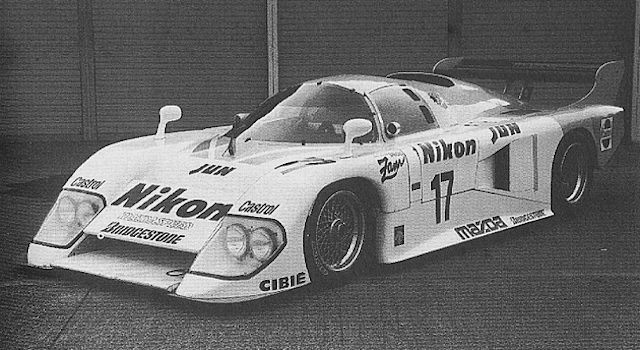

In 1985, Mazda commissioned Nigel Stroud from England to design that racer. The decision to part with Mooncraft was driven by the need to stay on the cutting edge of racing technology, of which England was the epicenter. Stroud had an impressive history, with stints at March Engineering and Lotus. The car Mazda asked him to design was to specifically accommodate the new 3-rotor as well as future rotary race engines with even higher output.

The result was the 757, constructed by Mazdaspeed, that set the form for Stroud’s subsequent Mazda designs to the 787B. Mazdaspeed entered two 13G-powered 757s in the 1986 Le Mans. Though neither car finished due to transmission problems, the 757 would give Mazdaspeed a 7th place finish the following year as well as a podium spot for winning the IMSA GTP category.

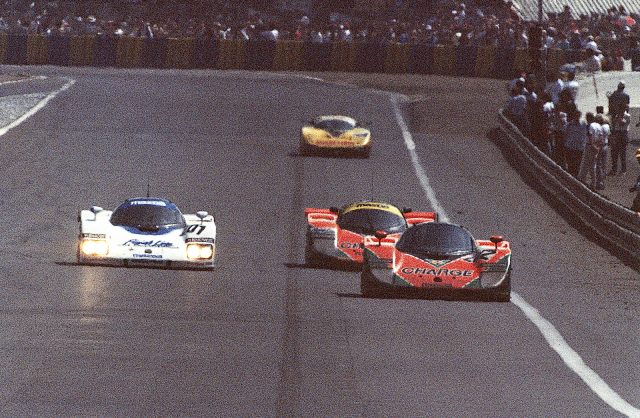

Then, Mazda upped the power ante with a 4-rotor engine to fend off competitors. The new 13J for the 767 put out over 500hp. Mazdaspeed also began a new and lasting strategy in the 1988 Le Mans: it would field two cars of the latest evolution along with one of the previous, more proven type. Both 767s and the 757 crossed the finish line in 1988. The subsequent 767B saw a bump to 630hp from the 13J-M thanks to a new variable induction system. Again, all three entered cars finished.

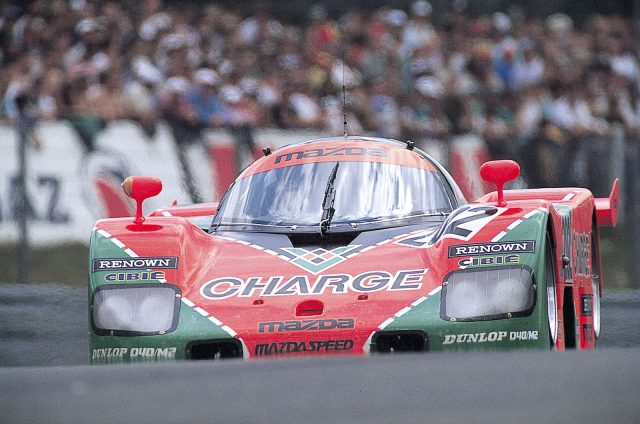

By the way, 1989 was another milestone year, at least cosmetically. The Japanese clothing company Renown became a sponsor and began supplying clothing for the team. Importantly, the iconic and radioactive orange-and-green livery—representing Renown’s CHARGE brand—debuted on the #202 767B and #203 767. The image of these vividly tartan’d Mazda prototypes screaming around the track would burn into the memories of countless enthusiasts.

Around this time, Mazdaspeed was becoming a seasoned Le Mans contender. However, to clinch outright win, they still needed more power. This would be answered by, incredibly, Mazda’s management from Japan. In 1989, Yasuo Tatsutomi, a Senior Executive Officer in charge of product planning and development, watched the three cars finishing 7th, 9th, and 12th and the team taking another IMSA GTP win. No small feat, but in his mind that still made Mazda a b-list contender. He spoke to team members about what was still needed, and Pierre Dieudonné, long-time Mazda Le Mans driver, said a hundred more horsepower. At the post-race debriefing, Tatsutomi promptly promised that additional 100hp by the following year.

The Ultimate Rotary Evolution: R26B

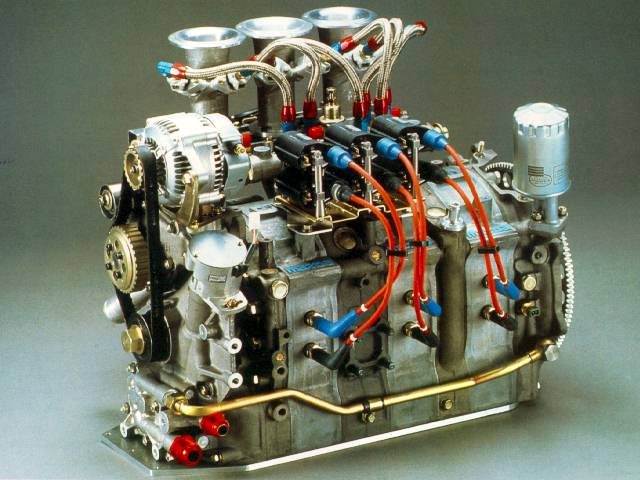

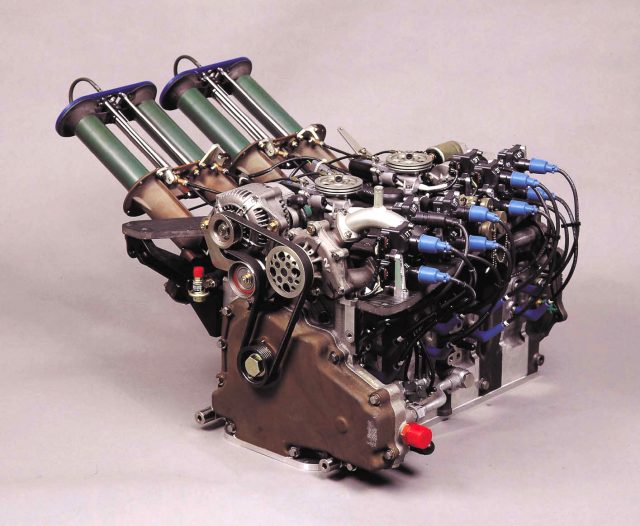

To deliver on that promise, Mazda developed an essentially new 4-rotor race engine, the R26B. By now, Mazda was heavily and enthusiastically involved in Mazdaspeed. The Motorsport Engineering department in Hiroshima had grown from two to eight full-time engineers working on race engines. In addition, Tatsutomi would transform Mazdaspeed’s racing development process into something more similar to that of a new production car project (i.e., making available all resources within and outside of Mazda to achieve the objective).

To make this possible, Tatsutomi appointed Takaharu “Koby” Kobayakawa as the program manager of racing — a role he was also serving for the development of the FD3S RX-7. On Koby’s team was Yoshinori Honiden, one of the engineers responsible for the 3-rotor 20B-REW in the Eunos Cosmo. Honiden worked with Kurio from Motorsport Engineering to achieve Tatsutomi’s engine mandate, which included not only the 100hp bump but also improved fuel economy.

The resulting R26B was smaller, lighter, more efficient, more powerful, and more reliable. It had three spark plugs per rotor, fuel injection at peripheral ports closer to the intake ports, and a variable induction system with telescopic intake manifolds. Output was 703hp at 9000rpm. Though this wasn’t quite 100hp more than the 13J-M, the R26B was no double a superior engine altogether.

To be continued…

We’ll have more on the 25th anniversary of the Mazda 787B’s historic win at Le Mans tomorrow, but in case you missed it here’s Part 01.

Photo credits: Mazda, 24 Hours of Le Mans.

I can’t wait for part 3!!!