Here we are at the end of 2016, twenty-five years since 1991. Think back, what do you remember of MCMXCI? The Gulf War? The end of the Bubble Era? Many of us remember the year quite fondly because it represented a kind of Cambrian explosion of JNCs. A vast array of automotive marvels replete with technological wonders and stunning designs emerged from Japan during that time. Among these was one car that many quipped to be destined for classic status from the beginning: the third-generation Mazda RX-7. This is how that car came to be.

The Lineage

The third-generation RX-7, along with the Eunos Cosmo, were the ultimate development of two long-running lineages at Mazda. In a way, both cars are direct descendants of the Cosmo Sport, Mazda’s first rotary production car and the world’s first car powered by a two-rotor rotary engine, with the Eunos Cosmo bearing its name and the RX-7 bearing its pure sports car form.

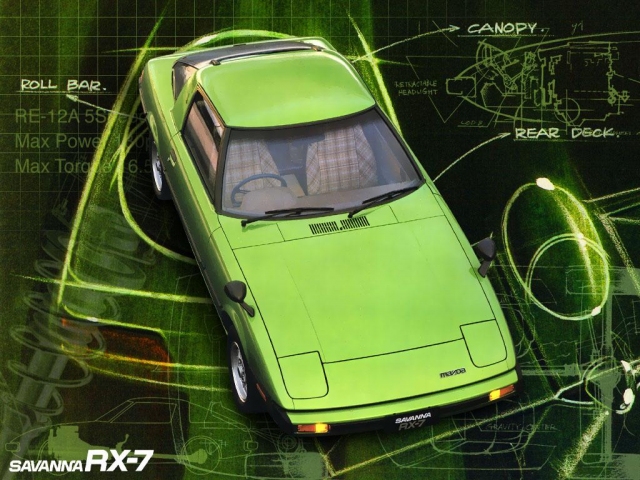

Though the RX-7 first appeared in 1978, it has some parentage in the Savanna, which was the RX-3’s name in Japan. The first two generations of the RX-7’s full name was “Savanna RX-7” in the home market, and also inherited the Savanna RX-3’s racing duties.

Curiously, the original RX-7 came to be partly as a result of the oil crisis of 1973. After the Cosmo Sport debuted in 1967, Mazda quickly extended the rotary offering into the rest of its lineup. Beginning with the common Familia and the aristocratic Luce Rotary Coupé, the rotary engine was an option on nearly every Mazda model by the mid-1970s. Even the Chantez kei car was developed with the rotary in mind, though the planned single-rotor engine never made it to production.

While such extensive rotary infiltration may be what JNCers and Mazdafarians daydream about, the oil crisis of 1973 spelled sales trouble for the lineup, as rotaries were not exactly miserly with fuel. Those who lived through the ordeal recall mint Familia Rotarys being common at salvage yards in Japan back then.

Faced with this potentially devastating predicament, Mazda took up two acts in response. The first was self-preservation through efficient economy cars such as the Mizer and GLC. The second act was a feat of outright heroism and ingenuity.

The rotary engine was deeply lodged in Mazda’s culture and spirit. It was and is a point of pride and a passion not easily relinquished. As such, Mazda was unwilling to turn its back on its engineering centerpiece. They worked hard on fuel economy and emissions cleanliness, but it was hard to counter the objective reality of development lag and even harder to change public perception.

The rotary engine, however, was perfect for a sports car. Its small dimensions would benefit both weight distribution and design, while its high-revving nature suited a lightweight canyon carver. And it had racing pedigree to boot. In the face of the oil crisis, then, a specialty sports car was Mazda’s answer to keeping the rotary engine alive.

If this were all dramatized by Hollywood, then about this time someone would be shouting, “It’s so crazy it just might work!” It was, and it did. Mazda had in fact been contemplating a rotary sports car for some time, and the proposal that carried forward was a lightweight compact sports car. The eventual Project X605 became the SA22C Savanna RX-7.

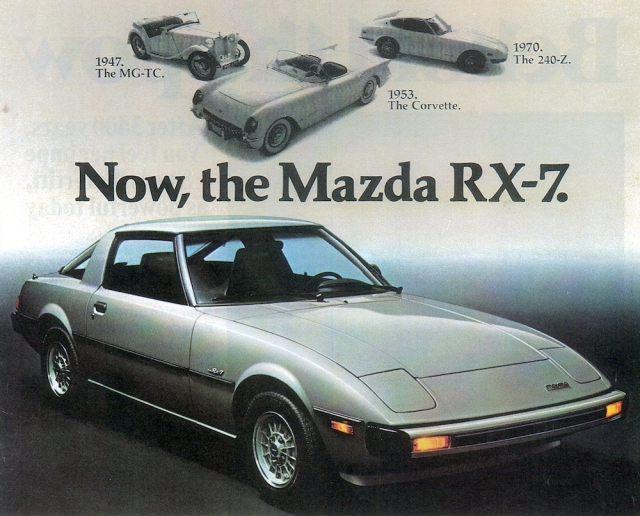

Unveiled in 1978 in Japan, it was an immediate hit with enthusiasts and the buying public alike, much like the S30 Z. It quickly launched into the competition arena to continue the rotary’s racing legacy, winning its class at the 24 Hours of Daytona at debut and Spa 24 Hours three years later. It would become the winningest model in IMSA racing history and launch a sports car legend. Not bad, or perhaps just what you’d expect, for a car borne from such challenging times.

The Progression

The first-generation RX-7 was a sports car sensation, but it was also a rather basic car. Penned by Matasaburo Maeda (father of Ikuo Maeda, Mazda’s current global design chief), it was clothed in innovative lines, but underneath it housed basic components such as a live-axle rear suspension. Indeed, this simplicity was part of its magic, but the competition, especially from other Japanese companies, was heating up by the mid-1980s. Thus the second-generation car, the FC3S, was to be much more sophisticated.

Debuted at the 1985 Tokyo Motor Show, the new RX-7 was larger, wrapped in a more mature design and loaded with contemporary technology. The suspension was now independent all around and featured two advanced developments. The first was the Dynamic Tracking Suspension System that used a combination of suspension geometry and special bushings to produce passive rear wheel steering. The second was the optional Auto-Adjusting Suspension with electronically adjustable dampers with three levels of firmness.

The engine now featured fuel injection — previewed on the first generation GSL-SE — with a six-port induction naturally aspirated version and an intercooled version with twin-scroll turbocharger. Even the pop-up headlights were trick, with a parallelogram mechanism that moves them vertically and allows them to function through the small windows in the bumper when lowered.

Being larger and more civilized than the SA22C, the FC outclassed its predecessor. Its performance and development enabled it to easily keep up with contemporary sports cars. In 1986, Takaharu “Koby” Kobayakawa became the RX-7’s program manager. Koby-san was one of the famed “47 Samurai” during the rotary engine’s development and one of the engineers who worked on the Cosmo Sport racing program at Marathon de la Route.

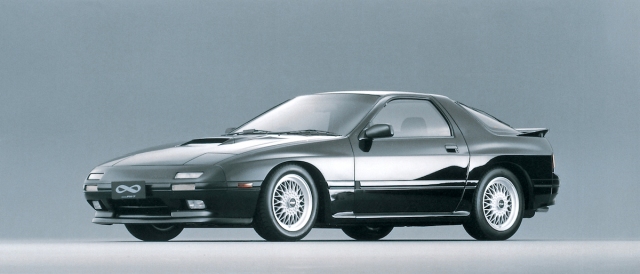

Under Koby-san’s reign came the Infini models, a series of four limited edition high performance “driving specials” in the home market, all of which were two-seater, manual transmission cars notable for suspension improvements. The goal was to sharply focus the sports driving side of the model through evolutionary development and to help develop the next generation car.

The Infinis were effectively previews of the third generation RX-7 as Koby-san pushed to extract further performance and dynamic improvements with each iteration. They were hard core sports cars, canvases for Koby’s vision and brilliance to shine through. An example of the final version, Infini IV, was sent to the US and tested by Road & Track in 1991. Their reaction: “Through the years, we’ve seen sports cars grow larger, softer, and heavier, which makes Mazda’s reversal of the trend even more exciting. Let’s hope that this Japanese-market Infini’s chassis is truly representative of the new generation’s.”

The Sports Car Marvel

Development of the third generation RX-7 began in late 1986 under Koby’s direction. By this time, the upcoming MX-5 Miata was already expected to occupy the lightweight and affordable sports car niche, thus clearing the way for the RX-7 to climb up the performance ladder as a specialty sports car. Members of Koby’s team included key people such as Takao Kijima and Nobuhiro Yamamoto — all three of whom would play important roles in the 787B’s Le Mans victory in 1991. Kijima would later lead the RX-7’s evolution and the NB and NC Miatas’ development, while Yamamoto would become the ND’s program manager.

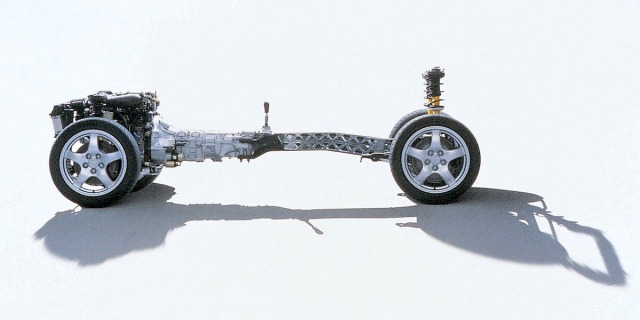

Koby-san led a focused team with a clear vision for the new RX-7: a high-performance lightweight pure sports car with little compromise. This included a weight reduction program dubbed Operation Z. Effectively, all parts, components, and production methods were meticulously scrutinized to minimize weight, ultimately shaving close to 250 pounds from the final car.

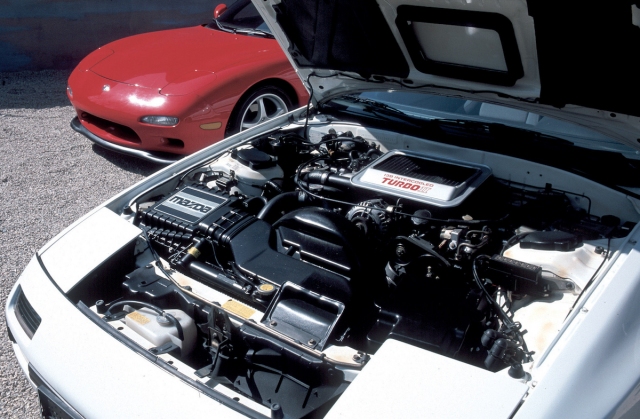

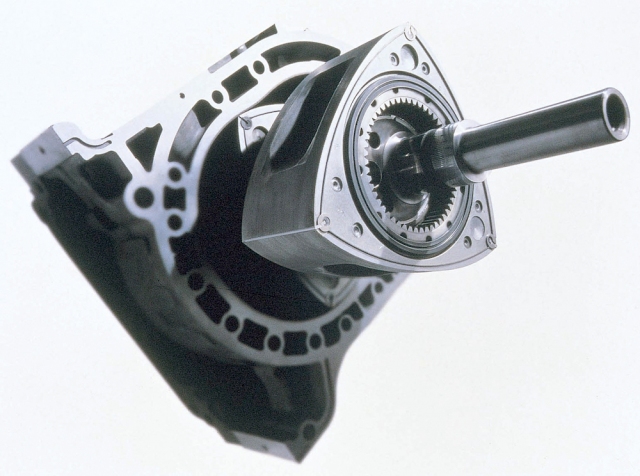

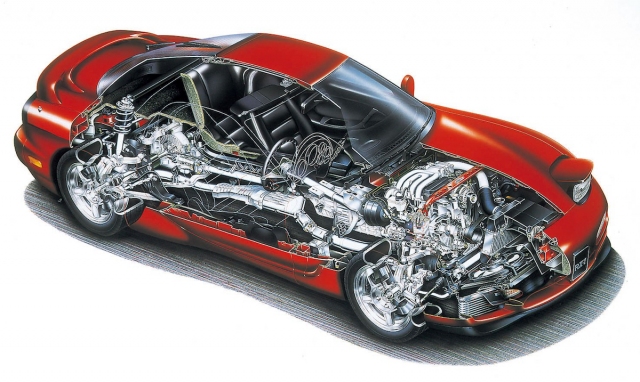

A power increase was in store in conjunction with weight reduction, and the new RX-7 was to adopt a sequential twin-turbo rotary engine like the upcoming Eunos Cosmo. The Cosmo was to have two- and three-rotor options, the 13B- and 20B-REW, but Koby-san rejected the three-rotor for the FD as it would have necessitated, optimally, a larger car.

The two-rotor for the RX-7, however, was not just the Cosmo’s 13B-REW with software changes. To suit sports car rather than grand tourer driving (i.e., frequent and sustained higher revs), the RX-7’s 13B-REW had different casting for the rotor housing as well as larger and faster-spinning turbochargers. The result was a higher output and redline for the RX-7’s engine.

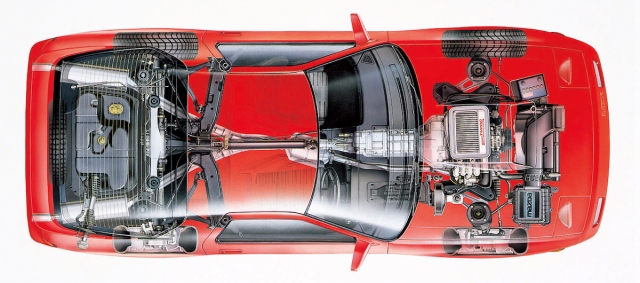

On the chassis, the new RX-7 employed double wishbones at all four corners. Ventilated disc brakes were used all around as well, and the Power Plant Frame that debuted on the NA Miata — essentially a rigid backbone that connects the drivetrain to differential — greatly improved structural integrity. The new car weighed in around 2800 pounds with an ideal 50:50 weight distribution.

In terms of styling, Mazda turned to four design centers around the world for an in-house competition: Hiroshima, Yokohama, Irvine, and Worthing (UK; International Automotive Design, as construction of Mazda’s design center near Frankfurt was still underway then). Proposals were submitted from all teams with different design interpretations of a flagship sports car under the directions of chief designer Yoichi Sato. The two finalists chosen were from Hiroshima and Irvine.

Curiously, the general theme of these two designs were somewhat opposite. The Hiroshima design was short-hood, long-tail, to evoke Mazda’s Le Mans prototype racers. Tom Matano, Mazda’s design chief at Irvine, anticipated this and decided to keep to the RX-7’s tradition of long-hood, short-tail. The eventual winning design came from Irvine and was developed by WuHuang Chin, an Art Center graduate. Further design work was a collaboration between Hiroshima and Irvine, resulting in one of the most timeless and beautiful sports car designs of all time.

The Market

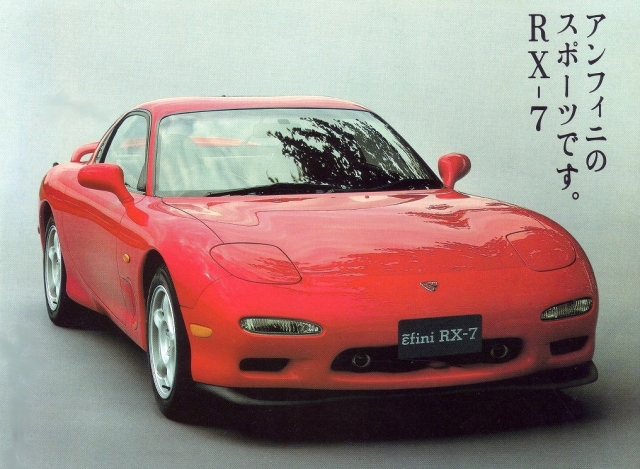

The FD3S RX-7 debuted at the 1991 Tokyo Motor Show, on a revolving rotor-shaped platform no less. It was marketed under the ɛ̃fini brand, one of the two premium Mazda divisions created for the home market at the time. The Savanna name was no longer attached. Three trims were offered at debut: Type S was the base model, Type R the sports model, and Type X the fully-loaded luxury model. The FD made its way to the US the following year as a 1993 model similarly trimmed as the Japanese counterpart (Base, R1, and Touring).

The press gave immediate acclaim, as it was one of the few next-generation sports cars that brought down size and weight and dialed up on the pure sports car formula. The new RX-7 would go on to occupy Car and Driver’s Ten Best list every year it was sold in the US. Its dynamic, power, balance, and design were all points of excellence, though the R1 was deemed a bit too track-focused by some American journalists.

The FD found in its peers sports car luminaries — Z32 300ZX, NSX, Supra, R32 Skyline GT-R, 3000GT VR-4 — all of which would eventually fall prey to two man-made disasters: burst of the Japanese asset price bubble and the SUV craze. By the mid-90s, sports cars and coupes, especially those costing upwards of $40,000, struggled to find buyers in significant numbers. The FD lasted in the US a mere three years, with the final supply of 1995 model year cars not selling off until 1997.

The Evolution

Though it was pulled from the US market after 1995, the RX-7 did continue on in its home market for quite some time. Having become the RX-7’s program manager in 1992, Takao Kijima carried the torch of RX-7’s evolutionary development. Like Koby-san and the FC’s Infini series, Kijima developed the even more sports-focused Type RZ, the first of which debuted in 1992. It featured suspension upgrades including Showa shocks as well as special Pirelli tires, a different gearbox and drive ratios, and a pair of Recaro bucket seats. Notably, it was the only two-seater (as opposed to 2+2) Japanese model at the time.

Numerous other special editions appeared in Japan, some celebrating the FD’s racing success at Bathurst in Australia. Many of these were effectively minor trim and optional packages, while the first major change came in 1996. The 13B-REW saw a 10hp increase in output, while round elements appeared in the taillights. The spoiler was replaced by a new “whale tail” design, and minor changes were introduced for the interior.

The following year saw the Type RS-R in celebration of the rotary engine’s 30th anniversary, featuring some functional equipment from the Type RZ. The ɛ̃fini brand was shuttered after 1997, and the RX-7 was marketed as a Mazda again…now proudly wearing the new “flying M” emblem.

The biggest change, however, came in 1999 with FD’s most significant facelift and a prominent adjustable wing of new design. The engine’s output was brought up to 280 PS in the high output models, while the interior saw further refinement with modern safety features. The Type RZ made a return as a limited edition sports model, and the RX-7 soldiered on with a few more special editions and finished production in 2002 with the Spirit R series.

The Legacy

The FD3S RX-7 was always destined to become a classic. Its singularly focused purpose throughout development is lore in its own right, and it represents the pure ideals of the sports car as well as the logical progression of its own lineage. Few cars are so meticulously molded with such care, beauty, and integrity — one can easily see that it was exactly what its makers wanted. Though many are eager to opine on its mechanical intricacies, even more hold the FD to the highest regard and desire in their hearts. It has become a genuine legend.

Here in the US, this is made apparent by the value of these RX-7s, though that may also reflect diminishing numbers of an already rare car. More than ever, this is a car worth not just owning, but preserving, for it represents a rare instance when passionate carmakers pushed for and got their dream car out into the real world. At 25 years old, it is now an official Japanese nostalgic car, but the FD is a timeless piece of design and engineering. With the future of the rotary engine uncertain and hurtling towards autonomous and electric vehicles, the FD RX-7’s beauty and pure sports car ideals could very well make it the last of its kind.

Images courtesy of Mazda.

No mention of Initial D? That’s probably the first taste of the FD young enthusiasts had.

Depends on the age group and interests. Many were shaped by Gran Turismo.

Mine was gran turismo never watched the show till I was alot older and was more about the ae86 inthough

Certainly the case for me – I’d been playing Gran Turismo for a decade before I’d heard of Initial D.

I’d say there was more exposure from the Fast and the Furious, at least in the USA.

In my case was when I played The Need For Speed (first version of the PC game) back in ’94… the yellow FD has been a favourite since then 🙂

I remember CAR magazine doing a twin test of a UK spec FD3S against a 968 back in 1992 and as a result have had a 2001 Type R Bathurst R for the last 3 years. No 25 year age restrictions in the UK. Other than a Racing Beat stainless exhaust, it is as it left the factory. A fantastic looking car and it puts a smile on my face every time I get behind the wheel.

Back when the FD was being developed on the Nurburgring, engineers were there alongside Nissan’s Skyline GT-R development team. Subsequently, said engineers felt inclined to make their car go around the track faster than the Nissan and didn’t stop until they did.

Awesome write up on the FD, I love mine so much.

I love my rx7. Sadly they are getting harder and harder to come by. If your looking at investing in one of these beautiful vehicles don’t buy one thats been modded and especially don’t buy one that’s salvaged (lol even if they tell you it’s due to theft,lol it’s usually a lie…Plus it’s still salvaged) Also try to stick to the manual transmission.

Although they ironed out most of the kinks by the end of the production run, Mazda never could get the bumpers to colour match very well! (yes, yes, I know, Plastics vs Metal, etc. etc.)

One of Mazda’s finest – such a good chassis. These cars are so enjoyable to drive even without the need for heavy tuning.

i would like to have fd chassis on my fc3s turbo 😀

At 25, even the FDs are now officially a Antiques. Having said that, my yellow FD still looks brand new, albeit a bit more aggressive with 17″ Fikse rims/275/40 tires….and it’s been lowered ~ 1 inch. People are always trying to get me to run it…very rarely I will if they become like a knat that needs to perhaps get swatted ;o) I enjoy having my sequential twin R1 as it’s a 10 sec car – I don’t get overpowered by newer cars that obviously the latest in various technologies. I do enjoy having the 5 Spd….I don’t think I’d buy a new car without a Manual – it engages you with the car unlike even the slickest Autos (ie Porsche PDK, etc). Go Rotary!

“It was and is a point of pride and a passion not easily relinquished. As such, Mazda was unwilling to turn its back on its engineering centerpiece.”

This, so much – by 1975 the Wankel had literally sunk NSU which held the patents and had been first bought out by and then disappeared into VW – technically the Ro80 held on until 1977 but everyone knew it was only a matter of time before it was dropped without replacement to expand Golf production capacity. GM – General Motors, then undisputed top dog of the industry, had walked away from its’ Wankel program without a single production rotary-powered car. Only Mazda had made it work, had realized any of the theoretical potential of it.

Thanks for a great write-up on a great car.

It’s hard to put into words how fun the FD is to drive, how eagerly it turns in, the exquisite cornering balance that responds proportionally to every minute throttle input, the little inertia drift when you get too optimistic in high-speed curves, the way it sits down on its haunches and blasts up the next straight, kicking again as the rotary gets a second wind above 4,500 rpm and the second turbo chimes in.

Yes, it rolls and pitches somewhat, but that just means you have to work with the weight transfer to unlock its’ true talents – the low centre of gravity means it never lurches or loses its poise. The whole car is so willing, the engine devoid of any harshness that it just eggs you on to drive it harder, waiting for the buzzer to shift up, downshifting in a flare of revs, trail-braking into the apex. The way it needs you, the driver to be fully engaged in the drive separates it from cars that are merely objectively fast, and makes it a true sports car.

Every time I see mine outside my front door, I consider myself so lucky that a band of dedicated car-nuts got away with making such an uncompromised pure sports car, and that I am lucky enough to have one.